|

|

Marks and memories:

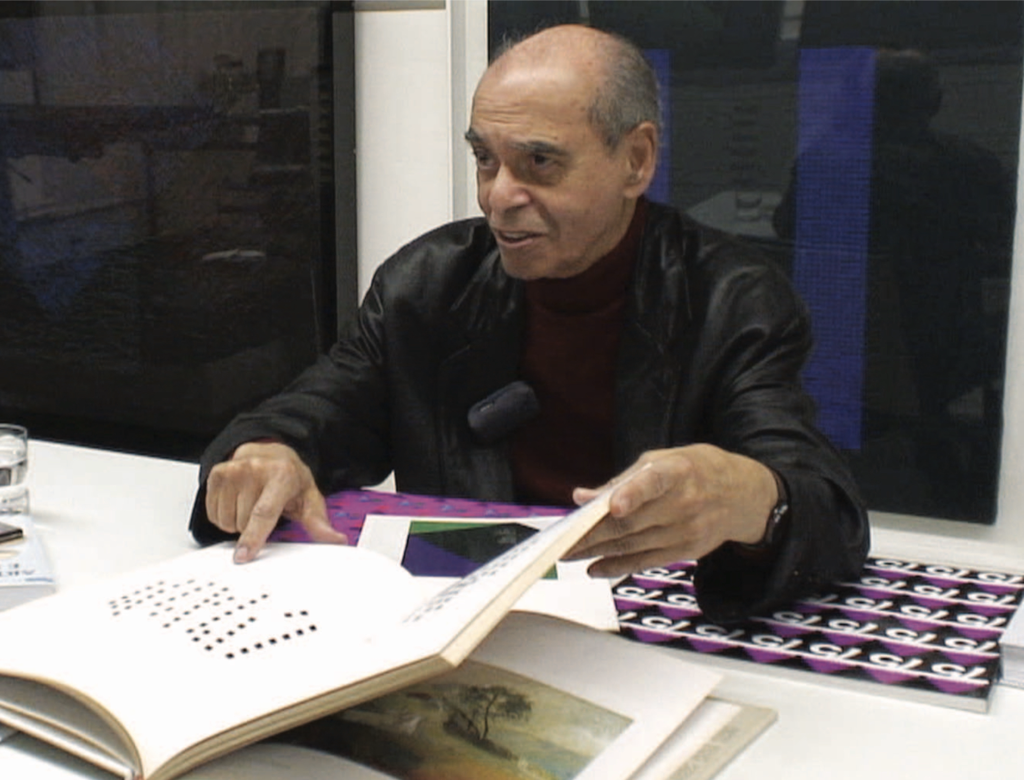

Almir Mavignier and the Painting Studio at Engenho de Dentro Lucia Reily, José Otávio Pompeu e Silva and collaborators Capítulo 5

Almir Mavignier: A master apprentice

Ana Angélica Albano

|

The master is not he who teaches, but who suddenly learns.” A small story of Meaningful Coincidence

The painting studio at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional at Engenho de Dentro was established during a moment of synchronicity, as Jung defined events that happen simultaneously without causal connections. It was born from a young hospital employee’s desire to have a place where he could paint and from the determination of a psychiatrist to broaden the scope of the Occupational Therapeutics Section under her management. More important than knowing who took the first step is realizing that the studio was born because of a meaningful coincidence. Today, the use of painting and modeling activities in the field of occupational therapy has become quite widespread in different contexts, a practice that has been discussed by several authors. Even so, the production of the patients at the painting studio at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional still arouses much interest and inspires research projects, both of scientific and artistic nature. Looking back at the early years of the studio, there seems to have been an indication that this was meant to be a numinous experience, described by Jung as “the influx of an invisible presence that produces a special modification of conscience” (Jung, 1978, p. 9): an alchemist’s studio where lead, the darkness of madness, would give birth to the luminosity of paintings, that upon arriving the rooms of the art museums, would alter many consciences. An uncommon symmetry seems to have been intensively active upon both major players in this unique story during the time they worked closely together. The passionate realization that they were entering unknown territory was shared by both, though their perspectives were quite different. For Dr. Nise da Silveira, it was about the discovery of the images of the unconscious; for Almir Mavignier, the discovery of artistic personalities in an unusual space and finding ways to help them flourish. Each in his or her field of knowledge sought out experts for support. Mário Pedrosa was to Mavignier what Jung was to Nise: partners in dialogue that validated their discoveries. It is interesting to note that among the Engenho de Dentro patients most studied by Dr. Nise until the end of her career, many began painting with Almir Mavignier: Carlos Pertuis, Adelina Gomes, Raphael Domingues, Emygdio de Barros, Isaac Liberato and Fernando Diniz. And even though the studio continued active and the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente harbors more than 350 thousand pieces today, it cannot go unnoticed that the artwork presented in both the catalogue Brasil: Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente, published in 1994 (Mavignier, Silveira, Cunha & Mello, 1994), at the time of theseu de Imagens do Inconsciente, published in 1994 (Mavignier, Silveira, Cunha & Mello, 1994), at the time of the 46th Frankfurt Book Fair and in the Brasil + 500 Mostra do Redescobrimento exhibition in São Paulo in 2000 (see Aguilar, 2000) were by the same patients from the beginning of the painting studio. Therefore, it seems to me that the strength of these works must reside in the conditions present at the very beginning of the work. From the point of view of psychiatry, Nise da Silveira’s observations and reflections are well known and have been broadly discussed and published, both in her own books and publications on the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente and in audiovisuals organized by the museum personnel, as well as in the Leon Hirszman films. Nevertheless, Dr. Nise was always quite cautious and avoided speaking of the works from an artistic point of view. She deemed that it wasn’t her place to do so: “I always maintained discretion about statements regarding the quality of the visual creations of the patients. That was the task of art experts. My task was to study scientific problems raised by their creations” (Silveira, 1982, p. 16). Her discretion, or her focus on unconscious processes, did not permit detailed information to be divulged about the conditions in which the production took place that enabled personalities such as Emygdio de Barros, Raphael Domingues and Fernando Diniz to mature artistically in a psychiatric hospital. When comparing the paintings Mavignier selected for the 1994 catalogue, in which his role was that of art editor, with those presented by Dr. Nise in the book Imagens do Inconsciente, for instance, one can clearly observe that Almir’s choices are based on artistic quality, while hers are based on scientific concerns. The patients are the same, but the selection is different. Therefore, it is clear that there have always been two points of view about this undertaking. It is now our job to bring to light the other side of the story, based upon the artist’s perspective. From my encounter with the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente At the beginning of 1975, a newspaper report on the work with painting that a psychiatrist, Nise da Silveira was carrying out with schizophrenic patients in a psychiatric hospital in Rio de Janeiro caught my attention so deeply that I began chasing after any piece of news that might lead me closer to this endeavor. I suspect that the report might have been published at the time of Dr. Nise’s retirement. In 1980, Funarte launched Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente, the first publication displaying images that were produced there and, in 1982 Imagens do Inconsciente, the first book written by the psychiatrist had been published. As soon as it arrived at the bookstores, I received two copies as gifts from two different people, because my interest in this work was so well known. Imagens do Inconsciente had a decisive role in my master’s research project, which I defended in 1983 and published in 1984–O espaço do desenho: a educação do educador–because, even though I was looking at drawings by children’s and teachers, which is quite distant from the universe of insanity that was the theme of Nise’s book, it was the way of looking at the act of producing images that touched me so deeply, as expressed in the following segment: Even though the child doesn’t have an intellectual understanding of the process, he or she is modified by the process of drawing. Dr. Nise da Silveira, working at the Engenho de Dentro Hospital with mentally ill patients in a painting studio observed the therapeutic quality of the act of painting, not only as a possibility of understanding the patient’s internal world, but that drawing and painting in themselves can be therapeutic (Albano, 2012, p. 20). I believe that at that time, though I was young, I already understood that I had entered into the intellectual territory where I belonged, cultivated by readings of Jung and Herbert Read. From that time forth, I followed with intense interest the publications, exhibitions, courses and lectures delivered by the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente personnel. Nevertheless, the greatest privilege was being presented to Dr. Nise in 1985, by a friend we had in common, Paulo Cesar Britto. I had the opportunity to visit her several times, taking her my first book and exchanging ideas and also observing the studio in operation at the time when Fernando Diniz was still working there. For me, a new fact in this story happened when I came upon the master’s research project (2006) by José Otávio Pompeu e Silva and when, for the first time I heard Almir Mavignier’s voice. I had always believed that the main variable in the painting project underway at Engenho de Dentro had to do with the fact that the activities had been oriented by an artist from the very beginning. It was clear, in Dr. Nise’s writings, that the patient’s production was not looked at merely as craft making, neither was it simply about making sure paints and brushes were available. She had always valued the fact that there was an artist present. And based on my experience orienting educational projects conducted by artists, I was convinced that Mavignier’s presence had been a decisive factor in the unique production that emerged in that setting. I was confident that the same dynamic that I had observed in the field of education would correspond to the occupational therapeutics setting. Artists, when they are interested in teaching, pay special attention to particularities of visual language and so they are better equipped to provide the necessary instruments and procedures for doing their job well. There were always meaningful comments on Mavignier’s performance, both in Dr. Nise’s and Mário Pedrosa’s writings in the Fundação Nacional da Arte catalogue: An important factor in the first phase in the life of the painting studio was surely the collaboration of Almir Mavignier. In 1946, Mavignier, who is today one of Brazil’s leading painters, had just started out painting and was a [hospital] employee (...) Mavignier developed a genuine passion for his new work, he never intended to influence the patients that attended the studio and, with rare openmindedness, he respected, admired and treated the residents of the psychiatric hospital on a person to person basis (Silveira in Fundação Nacional da Arte, 1980, p. 14). Indeed, Almir was not a monitor like the others. He was, perhaps, the only one who, when performing his duties perfectly instructed by Nise, carried inside himself an ardent and romantic belief that he transmitted to no one: the belief that inside the dark chamber of that schizophrenic dwelled a Genius. So the monitor-artist established an extra mission: that of providing his patients with the best possible conditions that would allow them to create freely, with nothing, absolutely nothing, to come in their way (Pedrosa in Fundação Nacional da Arte, 1980, p. 9). |

|

It should be mentioned as well that even Jung noticed the aesthetic quality of the paintings produced under Mavignier’s orientation; during the II World Congress of Psychiatry in Zurich in 1957, he made the following comment:

I was impressed by the paintings by the Brazilian schizophrenics, because on the foreground they had typical characteristics of schizophrenic painting, but on other levels, the harmony of forms and colors was not like the painting of schizophrenics. What is the environment like where these patients paint? I suppose they work surrounded by affection and by people who are not afraid of the unconscious (Pedrosa in Fundação Nacional da Arte, 1980, p. 10). In the book on the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente, published by Funarte, the special attention given to the pictorial language was already evident, but there are not enough descriptions of the production process itself to enable the reader to gauge how the work was carried out. Not only was the aesthetic quality of the artwork quite remarkable, but also the expression of uniqueness, the differentiation of personalities, not merely in the subject matter, but also in the particular way of building representations that characterized the overall artworks of each of the patients involved in the process. When I was able to have access to Mavignier’s interviews through Pompeu e Silva’s (2006) research, I was able to verify that his interest was quite diverse from what attracted professionals in psychiatry. As Mário Pedrosa put it so well, he was convinced he had found “geniuses” among the patients. And he spared no efforts in order that they might have favourable conditions to paint. Sometime later, when I was invited to participate in the project–“Almir Mavignier and the painting studio at the psychiatric hospital at Engenho de Dentro”–I had the opportunity of working directly with the interviews that were conducted with Mavignier, including those recorded in Rio de Janeiro by the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente staff in 1989, as well as the one he gave to Cristina Amendoeira in 2005 in Hamburg. Through these interviews, I was able to revisit the story that I had known for some time, but I came across another version, that was almost the same, though not quite. It was as if the spotlights had changed position, revealing other contours, bringing to the foreground new characters that had been in the background, suggesting alternative scripts. And just as in novels of many volumes the same plot unfolds many times changing each time the narration is carried out by a different character; before my eyes another version of the painting studio was unveiled, this time in the voice of the artist. For him, what was at play was not what was being painted, but how it was being painted: the originality of form and not the manifest content. The narrative that follows was built upon a selection of Mavignier’s responses to the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente staff in 1989 and to Cristina Amendoeira in 2005, in dialogue with texts that he wrote for the book that was organized about the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente in 1994 (Mavignier, Silveira, Cunha & Mello, 1994). My intention is to unveil the method Almir developed for the initiation into painting, while he also was in the process of becoming a painter. My aim is to uncover the principles and procedures that guided his actions, while trying to understand how the fact of his being an artist and not an occupational therapist affected the work at the Painting Studio at Engenho de Dentro form its inception. Searching for artists at Engenho de Dentro: Selection criteria In the introduction to the book Brasil: Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente (Mavignier, Silveira, Cunha & Mello, 1994), Mavignier wrote: The initial task of the studio was to discover persons interested in working with painting, in a search among hundreds of patients in hospital wards and patios. Only sheer chance led to personalities such as Arthur Amora, Emygdio de Barros, Fernando Diniz, Raphael Domingues, Adelina Gomes, Isaac Liberato, and Carlos Pertuis. What most concerned us, however, was not so much chance discovery, but the fact that chance might, by the same token, hide other personalities that might forever remain unknown. This frustration made us search all the more (p. 19). My first surprise: Mavignier could choose the patients who would participate in the studio. Before long, he did not only work with those patients that had been referred by psychiatry. Evidently, the studio must have received some referrals by psychiatrists, but at first, he was allowed to select them. Not only did he select them, but he set out to find people interested in painting. As a painter, he believed his advantage was being capable of identifying those who were able to paint: “as a painter, I could predict; and I sensed who could paint” (Mavignier, 1989). Here I see a parallel with artists when they are engaged in education: there is a tendency to focus their attention on students who stand out in art and, frequently, prefer to work with only those who have shown a special interest for the field. After nearly forty years, convinced there were other artists in the hospital, Mavignier was still sorry that chance did not allow him to find them. Knowing the psychiatric hospital environment as he did–having been employed there–he must have known that it would not be an easy for the patients to clearly express their wishes. We started our work, but the problem was how to find people, do you see? Because there were two concepts–I was the artist; deep down, I was mainly interested in art and Nise was a scientist and she educated me–“look, this isn’t a school of fine arts, it’s a such and such school and we shouldn’t influence anyone, only create an environment in which they can work.” But how to discover these people? So I started walking. I would go out into the courtyard, looking at all those people, naked people, terribly hot, see? I looked: “that one looks like an artist, that one doesn’t It was completely insane, idiotic, but that is what happened, reading in their faces those who might... I mean, it is possible to read a certain sensibility, it’s written on their faces, and that is how I searched (Mavignier, 1989). Even though he knew he was not at an art school, he was concerned about making a place for himself where he too could develop his own painting. Therefore, he looked for “colleagues”, patients who looked like artists. He himself was aware that “it was completely insane, idiotic”, considering the psychic conditions of those patients. My job was finding artists; I know that it was not an art school, of course, it was an occupational therapy section, but I was not a psychiatrist. I was an artist and I was interested in discovering hospitalized artists. For me, my interest was discovering hospitalized artists; my impression was that there had to be artists there. I was not interested in just anyone who showed up to do occupational therapy and then afterwards simply went away. I wanted to find artists. There were artists, there had to be artists, just as there are artists outside, so I started looking for artists (Mavignier, 2005). He decided to look for artists that were already engaged in some kind of artistic activity and through the indication of a nurse, he found Carlos: One time I entered a very clean ward, very clean, because the courtyards were full and the wards were well kept. It was the philosophy and approach of the caretakers. So I asked one of the nurses: “Do you know anyone here who has been painting, that does [artwork]?” |

|

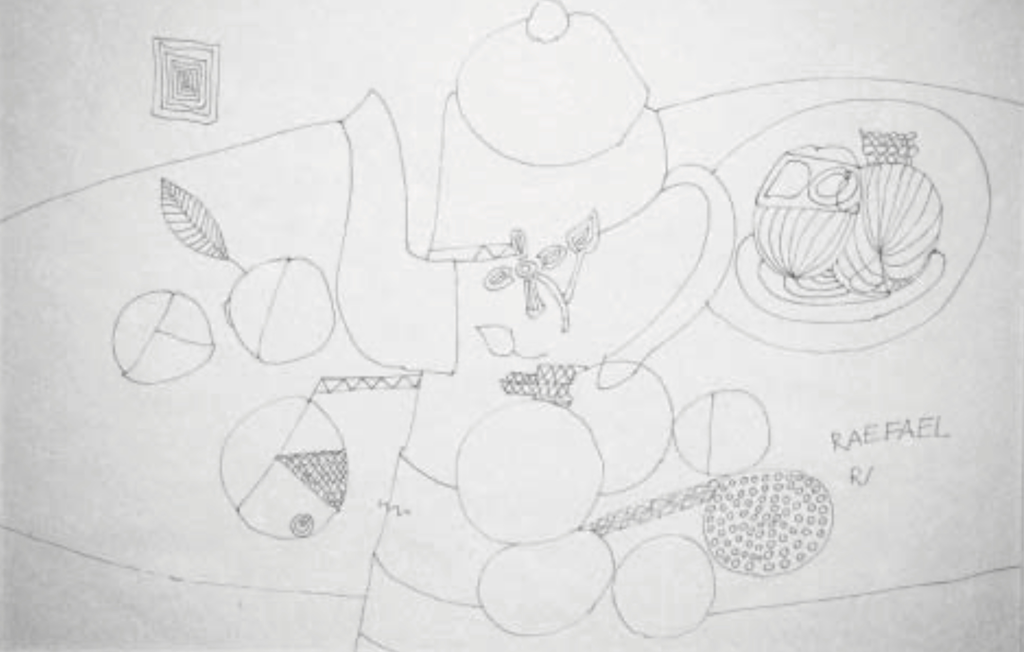

“There is a madman here, and under his bed he fills a box full of toilet paper squares with strange things drawn on them.” It was Carlos Pertuis. So he said: “Don’t you take him away from me, because he is a good worker, he’s very good, efficient, don’t take this man away from us.” So I saw the boxes with the fabulous drawings on toilet paper, variations of fruit transformed into faces... I made one of these drawings into a poster for the exhibition at Zurich (Mavignier, 1989).

Despite the nurse’s resistance, who wanted him for cleaning the infirmaries, Carlos was taken off to the studio. He soon began painting and produced a great deal during the time he spent there. Where the nurses saw strange things, Almir recognized fabulous drawings and he sensed creative potential that would later reveal strong paintings of a very characteristic style. “He arrived and started working. It wasn’t about being interested or not being interested. He was there and he started working, talking a lot to himself” (Mavignier, 1989). Mário Pedrosa described Carlos as “a man with precise contours, clear well-marked forms, in which almost nothing is shaped and his style is given by the play of contrasts and requirements of symmetry.” (Pedrosa in Funarte, 1980) Confirming Mavignier’s prediction upon seeing the content hidden in the box, Carlos’ work was later recognized, exhibited many times, commented on by Mário Pedrosa and widely analyzed by Nise da Silveira. Furthermore, his work was given special attention in the documentary “A barca do sol” by Leon Hirszman (1986). |

|

|

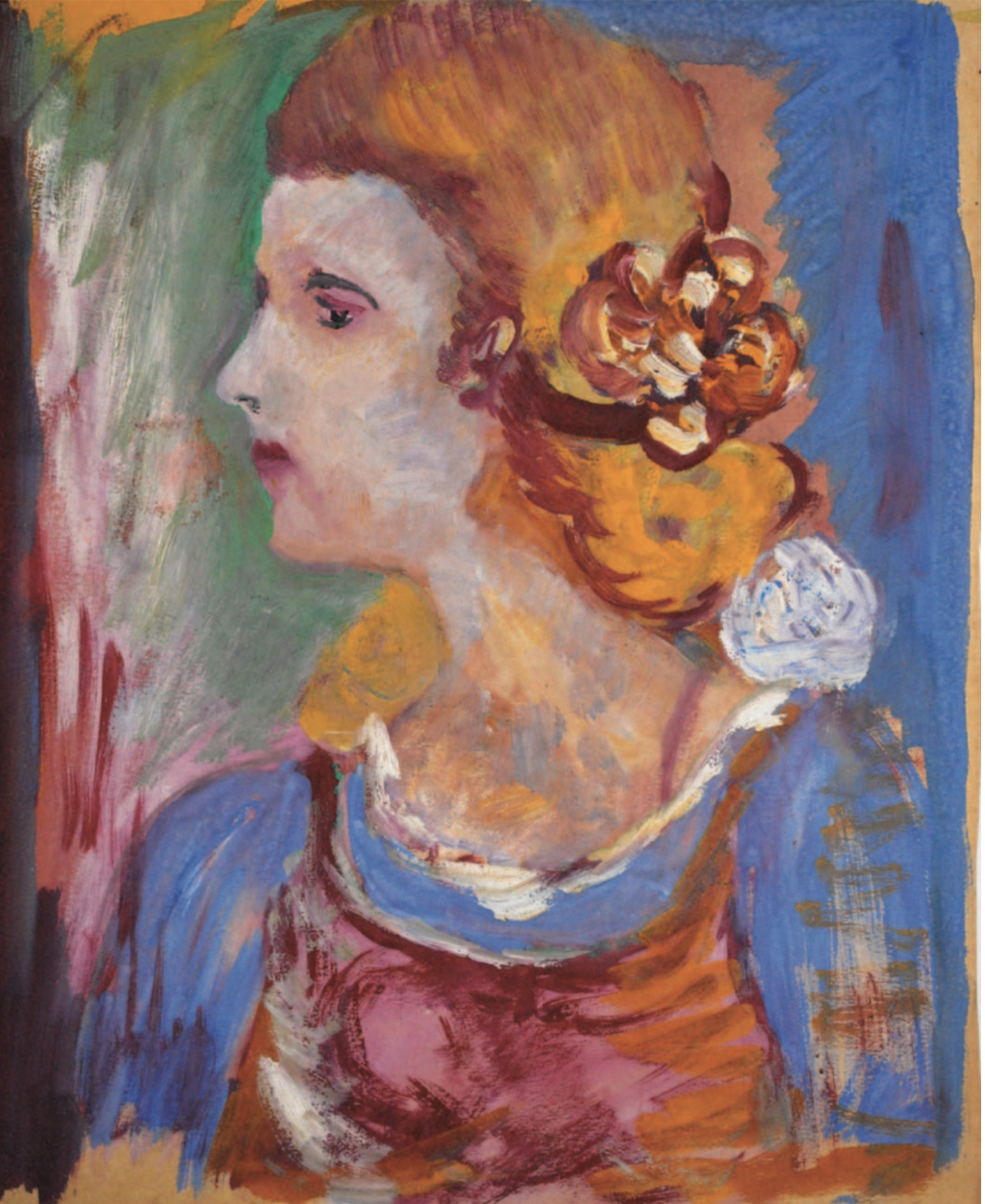

Still looking in the infirmaries, Mavignier heard about a woman who was very aggressive, but who made dolls. Almir decided to ignore the information about the aggressiveness because he was interested in meeting the person who created dolls. In this doll maker, he foresaw a sculptor:

and I heard about a very dangerous woman in one of the neighboring hospitals, a woman who made dolls. What interested me were people who did anything, to me, making dolls was already an act of creation. So they warned me, “look don’t take that woman, she beats up her companions, she is a very aggressive woman, everyone is afraid of her, she hits other peo l , you’re going to have problems in the studio, don’t take her, don’t go pick her up, it makes no sense.” But at that time my interest was in having artists, the one that made dolls, I was first interested in the fact she made dolls, aggressiveness came later... (Mavignier, 2005). Here is evidence that the patient selection criteria included the act of creation, with no concern for the object being created. Adelina’s dolls were a sign for him to invite her to the studio, and even though he had been warned that she was dangerous, he gently walked her to the Occupational Therapeutics Section protecting her with an umbrella. And it was raining that day, so I had the idea of taking an umbrella for protection, (...) I didn’t let the nurse bring her, (...) I wanted to do it. When I got there, I met a huge woman, fat, she didn’t seem dangerous, she could have been very strong. I was very skinny, and there was no attendant, I was alone. (...) The fact is that I took her under my umbrella. I protected her–obviously opportunistically because I wanted her to work. So I started with a little kindness, maybe I exaggerated a little, but I showed her that there were people who were kind, because I knew they were treated like animals. So, protecting her from the rain, Adelina was huge, protecting her from the rain, I got wet, but she was protected so it didn’t rain on her. This was a strategy, because I wanted to win her over without aggressiveness, and she behaved very well, like a child. She would come like a child, gentle, delicate, very feminine. All of that fat, very limp, soft, quite agreeable, and Adelina never gave me a hard time [emphasis added]. That way of going to get Adelina overcame her. There was no problem with me, she didn’t talk, very introspective, she would draw or do modeling with great force. The same force that she used in the infirmaries to beat up her colleagues she used on the clay, making forceful shapes and then I saw Adelina’s first forms: a sculptor (Mavignier, 2005). Literally and symbolically, Mavignier went out into the rain and got wet along with Adelina. While he protected her from the water and from her own aggressiveness, he won her over. He said it was a strategy. It seems to me to have been more of an intuitive act, and no doubt a courageous one, considering he was a young man who was just beginning the role of “art teacher”. The way he remembers this encounter reminds me of Jung’s observations: “I suppose that they work surrounded by affection and people who are not afraid of the unconscious.” When presenting Adelina’s work, Mário Pedrosa wrote: When she started attending the painting studio at STOR, she was without a doubt the most tortured and violent among those attending. Before she began painting, she would squash clay with her powerful hands, and in a flash she gave us some impressively archaic sculptures, for which we were to find a parallel in Neolithic Cretan artwork from thousands of years ago (Pedrosa in Funarte, 1980, p.146). Determined to find patients interested in art, he did not limit himself to the infirmaries observing those that “looked like artists”; he also resorted to reading the paTtients’ files, and this was how he found Raphael: I read in his file that he had enrolled in a painting school I don’t know where; that was Raphael. He painted, he drew things no one understood, he drew and did those stereotypical structures. And that is how Raphael showed up. About Fernando Diniz, I don’t remember exactly how he appeared (Mavignier, 1989). However, not all were “found”. Some just showed up and just set themselves up to work, which is what happened with Isaac, who came with his mother: Later other people showed up; one was always there, who came and peeked in. I saw an old woman beSside him, always with him, an old woman behind him, and one day he came inside and started, he sat at the piano and began to play, marvelous music, a little impressionistic, he laughed and he started with some brush strokes. That was Isaac (Mavignier, 1989). There were extraordinary types; they walked around in pajamas, walked around freely. Isaac walked with his mother. She had herself committed; she slept there, because she was a mother, a maternal complex. She was there, she didn’t abandon her son, she was always present... (Mavignier, 2005). Isaac’s artistic expression manifested itself in this first encounter through music, moving on to painting later. “Isaac painted with pleasure, slowly. He expressed less interest in painting than in the piano, that he played by ear. Without knowledge of music, he produced melodies reminiscent of Ravel and Debussy” (Mavignier et al, 1994, p. 26). He painted portraits and landscapes that, according to Mário Pedrosa answered “to the same appeals of subjectivity as the portraits. Indeed, these are not without an intimate quality and their chords of color tend to dissolve, toned down to the same musical atmosphere” (Pedrosa in Funarte, 1980, p.146). |

|

|

Emygdio began attending the bookbinding workshop and Almir discovered him when he becomes aware of a small watercolor with impressionistic brushstrokes that he had produced:

Emygdio was in the same hospital as Adelina. Hernani, my colleague, was the monitor at the bookbinding workshop and he discovered Emygdio. When he went to pick up the patients, including Adelina, he noticed Emygdio sitting in a corner watching Hernani and the group who were on their way out. Then one day Hernani brought one more patient. ”Hernani, what are you doing? We don’t have any material, nothing left and you bring one more!” “Look, I didn’t have the courage, I would go get them and he was in a corner and he looked at me with his big eyes and I couldn’t bear it. I had to bring him to bookbinding. (...), but he isn’t interested. I brought him to you, maybe he’ll be interested.” “But we don’t have anything else”, I said... (...) but when I saw that little watercolor... an impressionist−that was my advantage, I wasn’t as a painter, I had schooling, I knew what it was... like any student that has contact... I could read, as I painted, I mixed colors... So Emygdio was a revelation to me and I started buying material for Emygdio, bigger and bigger canvases, not like the others [emphasis added] (Mavignier, 2005). I knew this story from the version Dr. Nise used to tell. She ended her account with the following comment: And what happened to that man who spoke to the monitor with the language of the corner of his eye? His psychiatrist told me it wasn’t worthwhile assigning him to any activity because he had been hospitalized for 23 years. A chronic case, very deteriorated. Nevertheless, Emygdio went to the bookbinding workshop where he soon learned to do bookbinding (he had been a lathe machinist before being admitted), and soon preferred the painting studio. He painted pictures that surpassed the scope of psychiatry and are now recognized as part of the national artistic heritage (Silveira, 1982, p. 67). I always paid special attention to this episode and even mentioned it to Dr. Nise during one of our meetings. But I focused on the quality of the monitor who was able to read the patients’ eyes without realizing the patient in question was Emygdio. Today I read the same story in a different way because I have elements that weren’t available to me before. Considering Emygdio’s chronic state, it would be very improbable that he simply would have “preferred” the painting studio, unless someone had taken him there. Once again, there was the intervention of the monitor that was good at reading his eyes, who introduced him to Mavignier, who in turn welcomed him after observing a watercolor: that little watercolor... an impressionist − that was my advantage, I wasn’t ignorant as a painter, I had schooling, I knew what it was... One painter recognizes another when they meet. Mavignier recognized a painter in Emygdio and he took steps to enable him to develop his painting under the most favorable conditions, albeit inside a psychiatric hospital. There lies the difference of an artist who is also a teacher, because not all artists are so generous and ready to help talented people who cross their paths. In the words of the artist Tuneu, I recognize the same quality that I highlighted in Mavignier’s observations: I really do not think that I can transform someone into an artist, but if I behold an artist in the person, I must have the dignity to make this come about. We can spot artists and facilitate or repress their development. Because many people behave in the opposite manner, because they feel a mortal jealousy and demolish the artist the person has inside himself (Tuneu in Albano, 1998, p. 27). This is where we begin to delineate the kind of experience that happened in that setting due to the fact there was an artist working with the patients. An artist who began to develop as a painter and a teacher, and who recognized and valued talent when he found it. |

|

|

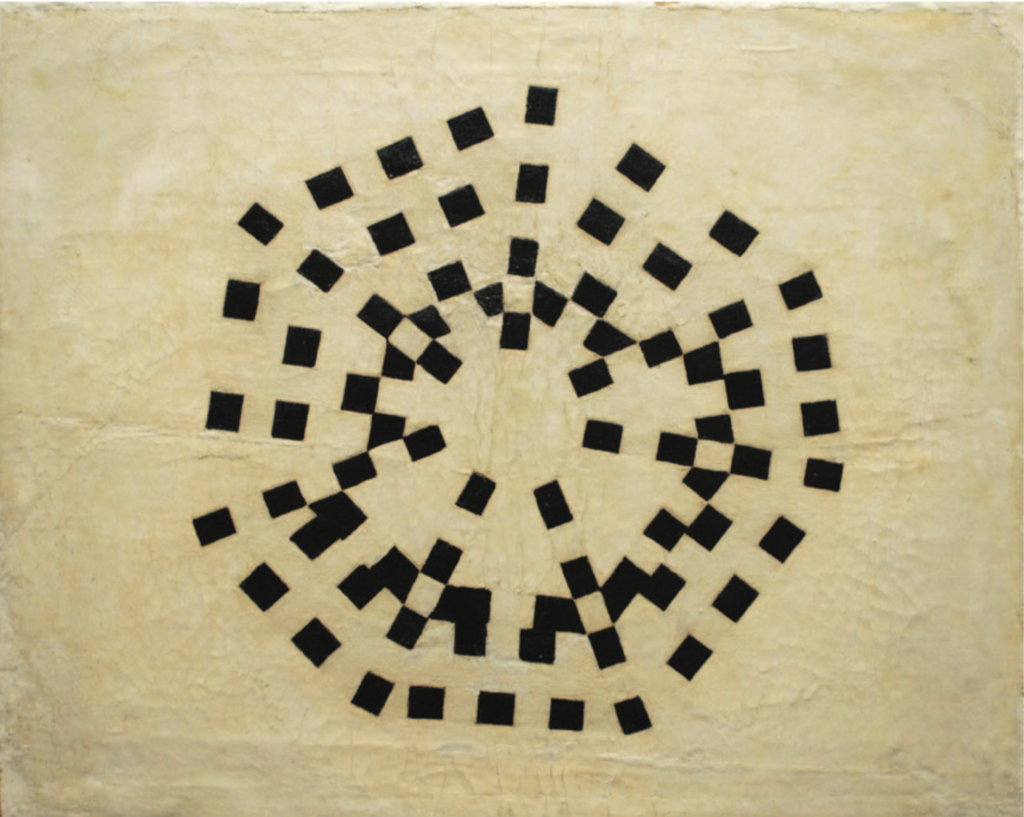

The artists Almir Mavignier discovered

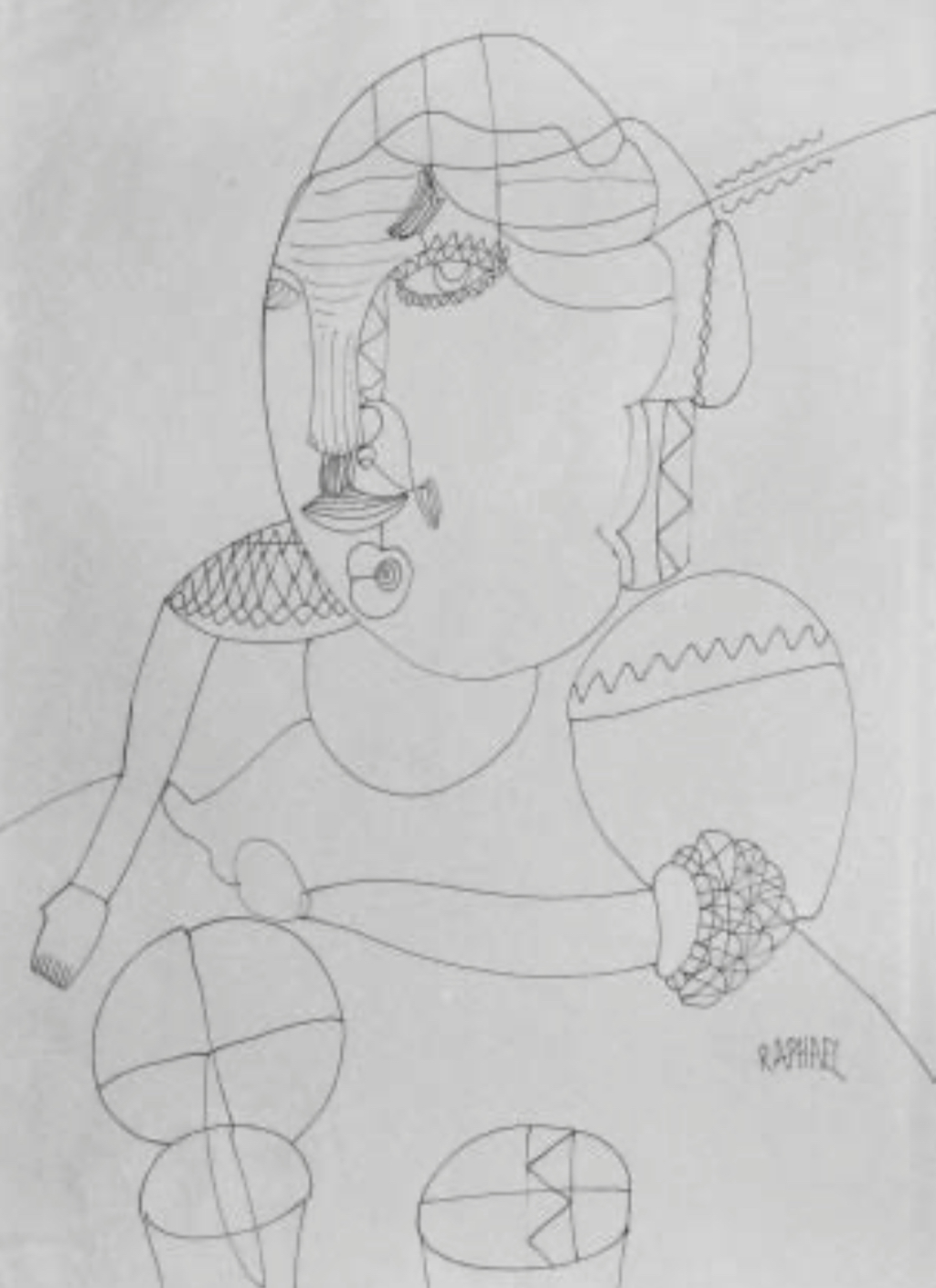

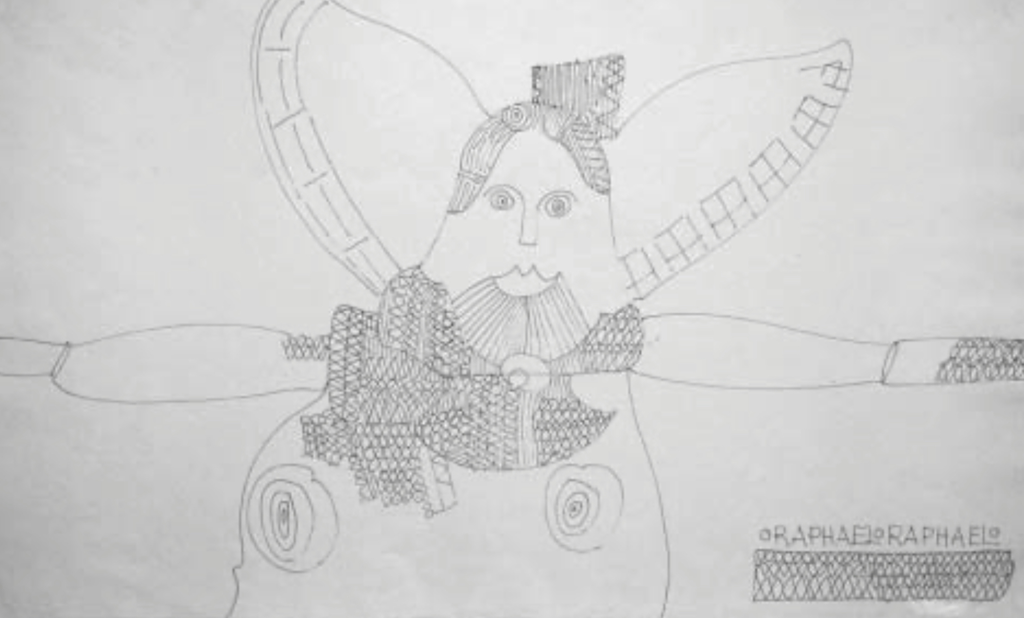

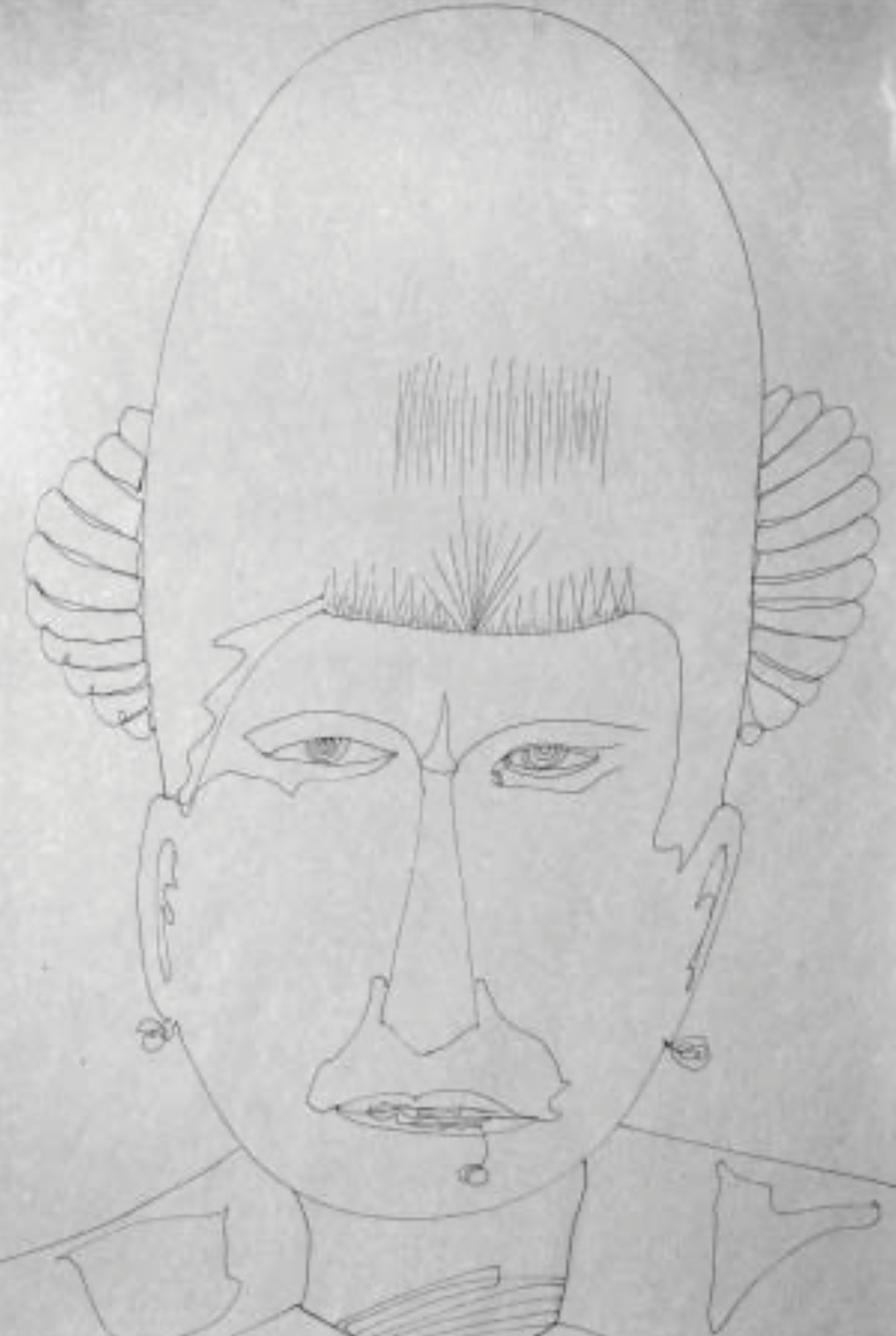

Carlos, Adelina, Isaac, Emygdio, Raphael, and Fernando are names mentioned in all of the interviews, though some appear only in brief responses to the interviewers. For this reason, I do not have enough material to comment on their stories. There were other names that appear briefly, and from Mavignier’s description, “they produced drawings of little importance, they were not artists. There were artists and those who just drew, that kept busy, busy being busy.” (Mavignier, 2005) So among those attending the studio, he distinguished between the “artists” and the “occupational therapy patients”. In the interview, and also in the book he helped organize, he dwells on and further describes the stories of those he considered to be artists. Raphael and Emygdio, who are the most important to him, end up occupying almost all of his interviews. The artistic importance of the artwork of both these patients is quite evident to Mavignier and it is easy to discern that he is proud to have discovered them. It is intriguing that one patient is never mentioned by Dr. Nise: Arthur Amora. His paintings are featured and are the first images of the book “Brasil: Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente” (Mavignier et al, 1994) and they are also commented on in the 1989 interview to the Museum staff. All that is known about him is that his passage through the studio at the end of the 1940s was brief and that he painted a sequence of dominoes that Mavignier offered him as a stimulus. No clinical data is presented, not even his date of birth. His paintings are of impeccable geometry, which is uncommon in schizophrenic patients; they appear only in this publication and are mentioned briefly in the 1989 interview: one thing I have a hard time explaining is the reason for my having in Hamburg two oil paintings by Arthur Amora and six paintings, six drawings by Arthur Amora that are of great importance because he was the only concrete painter... I have never stolen, I am not a thief, but I have them, I don’t know how... I have them over there, and it is something that puts me in a difficult position. (Annotation by delmar mavignier: Mavignier returned all works by Arthur Amora to the hospital) Amora appeared like this: a guy came by who kept spying, that kind of thing... and Arthur Amora is the first concrete artist in Brazil, which cannot be said about Emygdio or about Raphael. I mean, this is important, I have said so several times, it has even been published in newspapers. [Roberto] Pontual published this (Mavignier, 1989). On the Way he worked: Principles and procedures The studio was open and people came and went as they wished. Isaac, for example, was not fetched, he was never fetched, he walked around in the hospital, he walked freely with his mother following behind him. One day he came in, he came in there, sat down and started to draw and play the piano (Mavignier, 2005). I suspect the hours Mavignier worked as an employee, together with his interest in having studio space where he could develop his own painting during work hours, might have been the contributing factors as to why the studio was always open to the patients: The patients worked regularly, and this contributed to their growing command of painting techniques. The paintings were completed without theoretical guidance and with no knowledge of how to reproduce works of art in order to preserve the direct projection of forms and symbols of the unconscious. Through the very characteristics of the people who were there, there was no reciprocal influence. Each painter concentrated entirely on his or her own work, which allowed me to work with each as a painter, not as a monitor (Mavignier et al, 1994, p. 19). Here we have evidence of how Mavignier valued a work routine, followed by the realization that this encouraged their growing command of technique. This apparently simple observation shows that Mavignier didn’t look at the studio merely as an occupational therapy setting, but rather, he saw it as a painting “laboratory”. He was interested in the artists’ technical progress–artists he believed he had discovered–and he deemed it important to engage them on a regular basis. To work every day is a desire every artist harbors, though not many can to do so due to pressures of economic survival. These were confined artists we are talking about, but paradoxically, they were free to paint. And they demonstrated improvement. they were all hospitalized, but they were not patients, they were passionate. A patient is when you go into the doctor’s office and you have to wait for your turn in the waiting room, you need to be patient until your turn comes. No, they were not patients, they were passionate; it was the only thing they could do (Mavignier, 2005). He identified so deeply with the patients he considered to be artists, like Emygdio, that he deplored the fact they couldn’t keep on painting after the established hours: It was really hard when three o’clock came around; every one, at three o’clock, at two-thirty they were picked up because at three o ́clock the bus came to get them. If I didn’t go on the bus, I would continue my own painting, but they all had to go back o the hospital after two-thirty. An artist such as Emygdio would enjoy painting until whenever... (Mavignier, 2005). When Mavignier supposed that Emygdio would have liked to continue painting is evidence that he could identify with him. Time is certainly an important factor in maturing a work of art, nevertheless it is not the only factor to be considered and Almir also valued the working conditions of the setting. |

|

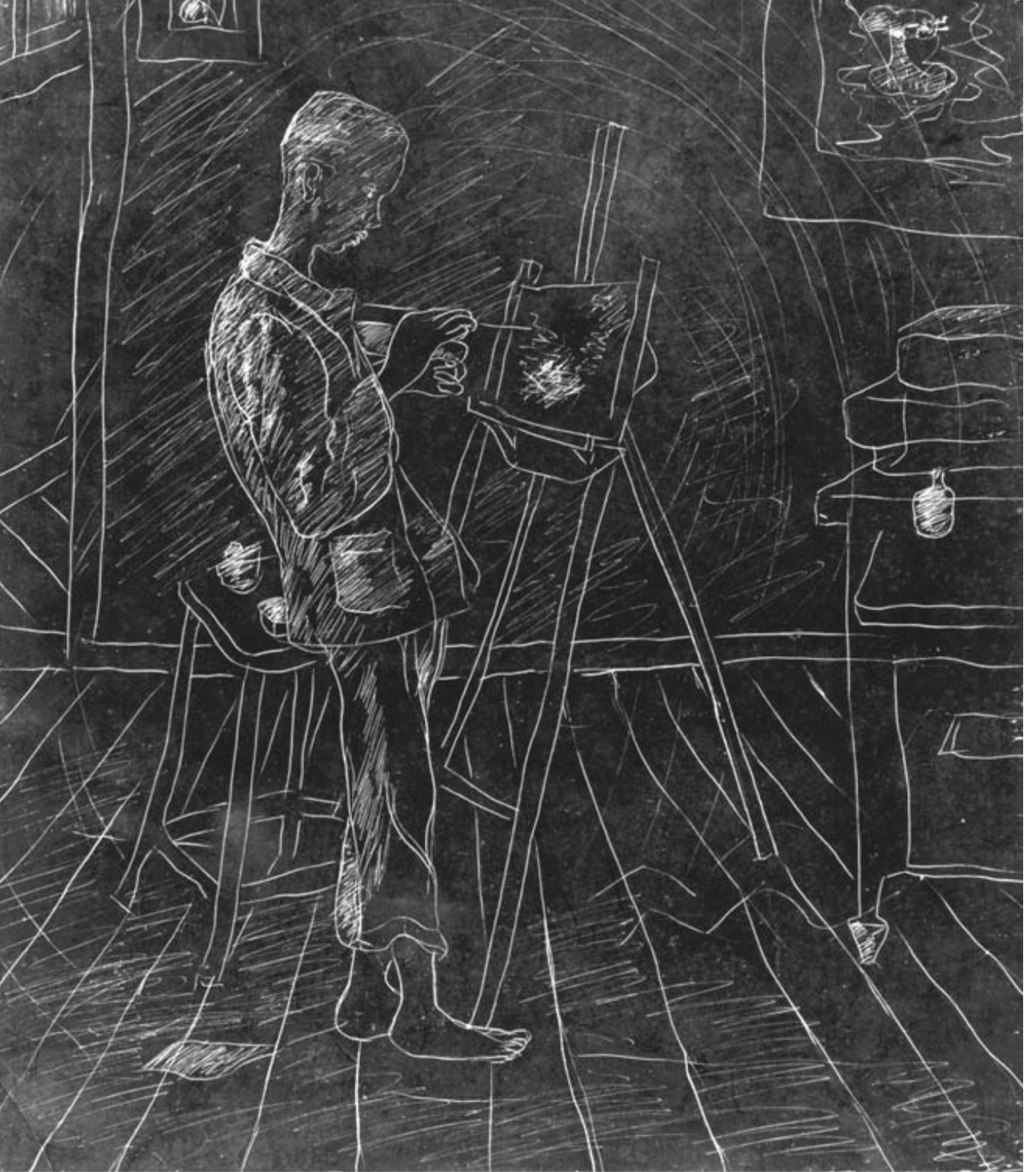

Ah, the room was quite spacious, a large room. There was a long corridor and this corridor led to several small rooms: Dr. Nise’s office was there as was the social worker’s. And the big studio was in the back, a large room, the patients worked in the large common room and there was a small room for me where I worked alone.

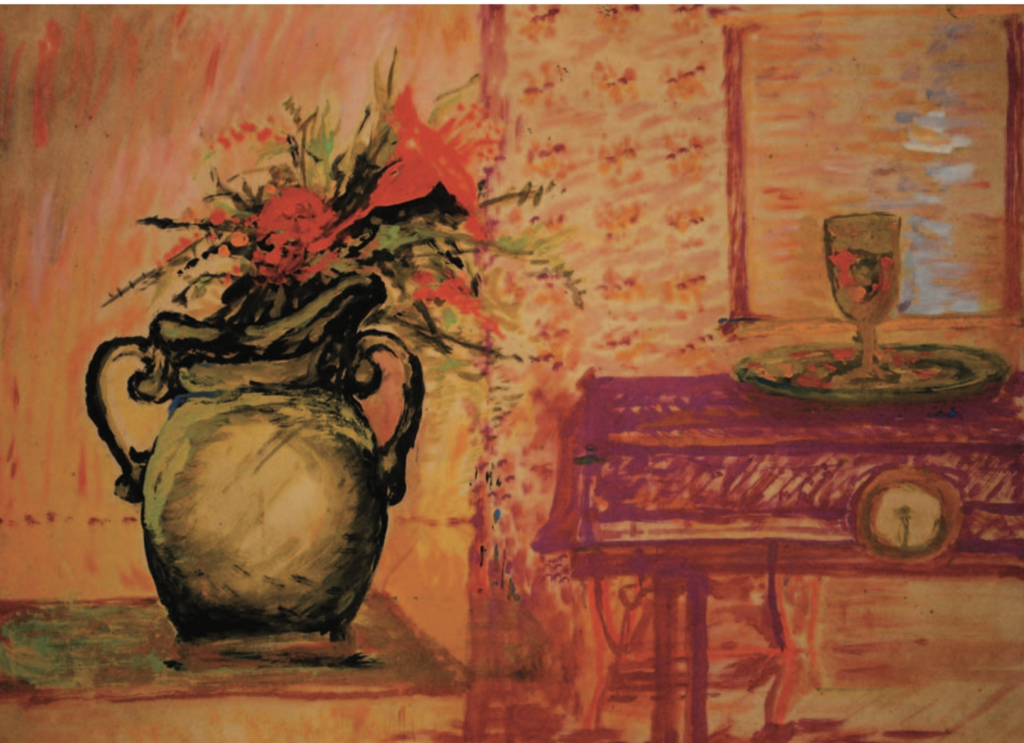

During the time I worked with the patients, I left Emygdio painting there, which was the only place Emygdio could work in peace, because in the common room there was a lot of agitation, people coming and going. And I thought, he needs an appropriate atmosphere to be able to concentrate and do his work. That is why he painted in my room, in my studio and in this picture with the windows, he did his first landscape, certainly in this room (Mavignier, 2005). His concern in favoring Emygdio with more adequate conditions for painting, Mavignier once again reveals how he identified with this patient. He recognizes or projects upon him his own need for time to paint and need for solitude, which are conditions commonly required by painters. How Mavignier managed his own privacy is a mystery to me. Perhaps his extreme youth accounts for his ability to supervise the patients and become enthusiastic about discovering artists while still being able to produce his own paintings, all of this happening in the setting of a psychiatric hospital. The orientation he received from Dr. Nise about not interfering may have allowed him to concentrate on his own work: |

|

Painting... You should paint when you want to, when you enjoy painting because you work in the hospital.

(...) Because they feel they are colleagues, when they see that someone is also doing it. Nise said: “don’t be an inspector”, loose that way of doing things. So I worked, I had my own studio there, I worked on my easel and they worked on their easels and they looked at my pieces and “well, he is insane, he is” and they respected me, “he is insane, he does whatever he wants.” (Mavignier, 1989). Though he wasn’t a therapist, Nise da Silveira instructed him and Mavignier considered that the fact that he painted alongside the patients favored his relationship with them because a positive transference occurred: “Because they feel they are colleagues, when they see that someone is also doing it. (...) They respected me, “he is insane, he does whatever he wants.” He worked alone and his main job was to technically equip the patients on the use of the material, like dissolving paint, cleaning brushes. Based on his own experience as a painter, he decided who needed more or less help: I commanded a small room for modeling and the big common room, I gave out the paint, the material, everything by myself. Each person had their own table. They drew separately, though all together (...) And that was interesting. I also painted inside my small room, but they could see me. They respected each other, there was no issue about copying, I didn’t hand out art magazines, I didn’t want to bring in outside influence that would affect their personal work (Mavignier, 2005). The main interference was showing them how water-colors dissolve in water and how oil paints dissolve in turpentine. Yes, first the use of material, and in Adelina’s case, that was enough, she produced and produced. That was also Carlos’ case, who produced and didn’t need anything else (Mavignier, 2005). |

|

|

Nevertheless, throughout the interviews, we began to notice that his interference was not restricted to the correct use of paints or the best way to clean brushes. He was an attentive observer, and he aimed to identify and encourage the kind of expressivity that he saw was characteristic of each participant. In Raphael, he recognized the master of line, a draftsman par excellence, and he endeavored to help him by furnishing brushes that fostered the development of other qualities in his drawings:

I gave him larger brushes so he wouldn’t have to draw the same kind of line [emphasis added]. (...) So here you can really see his ingeniousness, when we talk about the same brush, he did this, and without putting his brush into ink, he continued to do it. So you can see that directly from the inkwell, you can see, the wet brush, black, then here first, then here for sure, until it dried up [emphasis added] (Mavignier, 1989). Another time, Mavignier reported that he stimulated Raphael by arranging compositions of still lifes and encouraging him to paint them: and there were sessions with Raphael. So I would take him paper and he would draw, I would arrange the still lifes, a very kitsch coffee pot, there was a coffee pot, the same objects, an orange here, another one there, I set it up and said: Raphael, you do what you are looking at” Consciously, I kept to abstract words, what you see above or below, behind, but I didn’t say exactly, so as not to say, both eyes, for instance, or the nose or the ear, though maybe he would have wanted me to. Well, that was my awareness as an artist. Because you know, as an artist, Picasso can make as many noses as he wants to; Portinari, whatever hands he wants. My experience as a painter commanded me, guided me. Well, if he wanted to make six, seven fingers, he wouldn’t be allowed?–“Oh, you made an extra finger”, that kind of thing, no (Mavignier, 1989). In Emygdio, Mavignier identified a painter and he spared no efforts in encouraging his development, because he believed he was capable of great accomplishments if he were given adequate working conditions. Intuitively he realized that the patient needed space to expand his limits in painting. Once more, I would like to stress his condition as a master apprentice who is skilled at recognizing another in the other: My first surprise was, for instance, directly with Emygdio, I think Emygdio was the first, I’m not really sure... That first watercolor he did, I think I identified with the colors, I realized that he was a painter, a painter who approached impressionism... The more Emygdio worked, the more I was seduced by his work. I was aware that I was standing before a very important personality, I mean, psychologically for me, it was reduced to the point that I became a slave to it. I mean, I wasn’t a painter, I didn’t even know if I was going to be a painter or not... I read the importance of that painter in relation to myself, the importance was so great that I would say... I forgot about myself and devoted myself fully, the kind of devotion you also have, and all the material... Whatever material I bought for myself, I bought for Emygdio [emphasis added]. (...) I said “he needs room”, that is why it is important to have a painter here, because there are technical issues (...) and–from my point of view –, Emygdio needed space... (Mavignier, 1989). Mavignier constantly mentions that he was guided by his own experience in painting. Another time he confesses that the same experience caused him to suffer. It happened when he realized that a beautiful painting was emerging only to be covered over by another. Knowing when an artwork is finished is always a challenge for any artist. And at that specific studio, in which the issue was not to create works of art, the difficulty was in the eyes of who was seeing the production as works of art. I watched Emygdio painting and it distressed me because, for instance, there was a picture, he was painting, and then he went back and painted over everything. At what point could I say something? Naturally, I couldn’t say: “you stop now”, I couldn’t say that. So often, at a difficult moment, I would have a coughing fit, I would cough, I would sing whatever nonsense and I would yell something dumb, to see if he would lose his concentration, and he would go back to the where he was, so that was fine (Mavignier, 1989). He was aware that Emygdio was visualizing earlier experiences (and/or interior ones) and that only he recognized these visions as good paintings. Because this is our mistake: (...) we see this as a picture and it isn’t, these people don’t make paintings, they don’t make pictures, they visualize earlier experiences, so when they do an experience that has been visualized, they build another experience, which goes on top of the one they had already visualized. It doesn’t have that meaning [of a picture] (Mavignier, 1989). In this comment, he presents a paradox that seem to me to be inherent in the activity he was engaged in, which shows up in the contradictions that emerge throughout the interviews. Mavignier was constantly instructed not to interfere, and he was aware that he was working with psychiatric patients. Nevertheless, as a painter, he was skilled at identifying quality in the artwork that other monitors and even the psychiatrists did not notice. While admitting that the patients did not produce “paintings”, he wanted to preserve the works. To this end, he created strategies to conserve the works he considered to have been finished. Some of these strategies are bizarre, such as coughing and singing; some are reasonable, such as making more paper or canvases available to them. Dr. Nise never mentioned these strategies, and she might not have been aware of these procedures. But if today we have access to these images, we owe it to Mavignier’s slightly unorthodox pedagogical methods. |

|

Emygdio didn’t paint, he resurrected memories, he painted memories, he didn’t paint like a painter, he resurrected memories {...) he visualized experiences. This experience he would paint from left to right, and then he would start over from left to right with other experiences. I mean he would repaint, he’d cover over. His largest picture, a castle with figures,–there were several phases, there were several phases for this picture. While I watched, I watched and suffered, because he did marvelous work, and he covered it with experiences and marvelous things would disappear, fantastic things disappeared (Mavignier, 2005).

And I suffered, I suffered, I coughed because I couldn’t say “Stop!” I couldn’t say that: “Stop!” So I coughed, I coughed, avert that experience... I said “No, it can’t be like this”, and I discovered the trick. I bought several canvases and I said, “Look, Emygdio, when you are ready with one of your experiences, there’s more, there are other empty canvases” [emphasis added] (Mavignier, 2005). He furnished the painter, Emygdio, with canvases and the draftsman, Raphael, with paper. |

|

|

I used the following trick with Raphael: I always had a bunch of white sheets of paper and I would put them next to him and I would say–I knew Raphael didn’t listen, or that was my impression, but I would say, because the supposition was that he couldn’t understand anything because he was very abstract, very abstract was Raphael, so I’d say “Look, Raphael, when you finish (I hoped), when you finish, we have plenty of paper for you. You finish here and start on a new sheet.” So I was able to get him to fill in his drawings, he did it like this, in seconds, four, five. I would go: finished, now you. And he would go, he flew far away, because he was alone. That is what I managed with him; with Emygdio it was more difficult. He cuffed me, now I don’t know if it was Raphael or Emygdio, I don’t know if it was Raphael, because I probably exaggerated, so pow! (...) Possibly Raphael, because Emygdio wasn’t likely to do that. But I don’t know which of the two; I got cuffed by one of them (Mavignier, 1989).

The cuff expressed that the patient was unhappy about being interrupted during the oneiric process underway while he was painting. Once again, that shows that only Mavignier was able to see a finished painting while the image was in the making. It was hard working with Raphael because you never knew... He would do a drawing and start in on a stereotypical structure, and you didn’t know if he was completing a drawing or if he was messing it up. Because that was what we were wondering about: up to what point was he making a drawing? Drawings as we know them had no importance for him (...). At that time I was always afraid, because he would start to do this and then he would just easily move onto the face, and there I was suffering, because I knew “I can’t say anything to him”; “not on the face”, for instance. (...) His name, Raphael, I asked him to sign, he never signed, the name Raphael. I would say “sign your name”, like a kind of bridge, to indicate “acknowledge yourself.” (Mavignier, 1989). Mavignier’s desire to see Raphael recognize himself as the artist he deemed him to be by assuming authorship for his drawing, would once again cause conflict: interfere or not. Perhaps this conflict would have been addressed more appropriately if it were put differently: when and how to interfere. The constant tension between accepting Nise da Silveira’s instructions and the expectation to witnesses the obvious talent he had foreseen, he would find moments of relief when some kind of external interference enabled unexpected qualities to shine forth in the patients works. Well, Raphael began working, seated there, doing his stereotypes with a pen... I gave him watercolors and he didn’t say anything, he didn’t have anything to say. I was also instructed by Nise not to influence, not to do anything, to leave them alone. One day one of our colleagues, just someone from the hospital, said: “Hey, Raphael, all you do is those strange things, those crazy things that no one understands. Do a horse!” So he did a wonderful horse, right? Part that I don’t see here. A marvelous horse, it was his first (Mavignier, 1989). Naturally, his obligation with the patients was restricted to working hours. That is why the majority of the artwork that comprise the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente collection was created at the painting studio. I believe that his admiration for the exclusive expression of these patients can be explained by the fact that he spent his leisure hours with them as well. There is no mention that he may have worked with other patients outside of the hospital. Even when the interviewers were interested in other patients, he insisted on conducting the interviews towards Raphael and Emygdio, which confirms his admirations and enables us to approach the details of the didactics that he construed through an attention to the needs and possibilities of each of them. In Raphael’s case, the interference seems to have been more direct and incisive. He visited him at his mother’s house and he proposed very precise technical challenges: I would go work with Raphael and, at his house, in my free time from the hospital. Raphael did these drawings that I greatly admired (...). So Raphael worked at home a lot, he would go home, so after work, I went to Raphael’s house and I had sessions with Raphael. (...) And anyway, I was interested, because I wasn’t a psychologist, I was a layperson, definitely a layperson, though I was interested. I knew about the difficulties between mother and son, so several times I put the mother as his model, because I really wanted to see how he interpreted his own mother. So he did several portraits of his mother; afterwards, I wanted to see how he approached the issue of Christ, religion, how he reacted (Mavignier, 1989). In these “private classes” Mavignier seems to feel more at ease to experiment and challenge his “students” abilities and, finally, conduct the interference that he felt needed to be done. The discovery that Raphael could draw motifs from nature and thus emerge from his labyrinth of abstract structures, was indicative to us of a new mode of communicating with his interior world. He was in demand, he observed and he produced. Friends who accompanied me to see him draw such as Murilo Mendes and Mário Pedrosa were his models (...). As soon as he had met the request, he was lost in the dissociated structures of his own design (Mavignier et al, 1994, p. 62). At these times, greater discipline was required than would be possible at the studio with the group. That is why at one point Mavignier conjectured that Raphael may have rebelled against his requirements, representing him as a demon. |

|

Palatnik was always with us; I often used Palatnik as a model. Curiously, I was never a model myself. Because I never did any self-portrait, you know? I don’t like my own face and I didn’t like that, I didn’t want it, but one time he did a drawing that could only be of me, a horrible drawing in which I was a demon, because I urged him: do this, do that. I was unbearable, wasn’t I? With all those demands. And I know, it must have been me, because next to it is Palatnik’s portrait, and he was with me; I mean, it couldn’t be anybody else (Mavignier, 1989).

Working with Emygdio was a completely different story, consisting of providing experiences that could add different qualities to his painting without specific orientation. Emygdio, he went out several times. We did one trip to the Alto da Boa Vista. After this excursion, he painted the little waterfall–a marvelous picture–and also the Mayrink chapel. We did an exhibition in the city center and after this exhibition, he painted the Municipal Theater, but there was no request on my part, that is why I differentiate between Raphael and Emygdio. His things are fabulous, really brilliant, but he [Raphael], without that stimulus, he wouldn’t do anything. I mean, he was an artist immersed inside himself who had to be pulled out to be discovered. Emygdio was something else altogether, Emygdio did it on his own. [...] The cars he did at the Municipal Theater were not cars from those days. They were not the current style, they were from his time. If you pay attention to the cars, they were old automobiles. The Municipal Theater, on the other hand, yes, but he transported the time he had experienced (Mavignier, 1989). He makes an important distinction between Emygdio and Raphael’s work, pointing out that the first was more independent, so much so that he continued developing his painting even after Almir went to Europe, while the second never produced anything again of the same quality. The excursions, however, were not limited to visiting bucolic landscapes or cityscapes. He also took Emygdio to visit other artist’s studios, hoping to broaden his understanding of painting: Afterwards, I took Emygdio to Ivan Serpa’s studio, and Emygdio said “Ah, this how one paints nowadays.” Because I painted more or less like Ivan Serpa. We were both concrete-abstract painters, with geometric shapes. “How so, Emygdio?” He said “color against color;” he understood perfectly (Mavignier, 1989). In some interviews, Almir commented on how he understood the signs that an evolution in the language of Emygdio’s painting, which seems to confirm that his efforts to educate him artistically had had a positive impact: Mavignier: [I was talking about] evolution in the sense of treatment of form, in the treatment of structure. Like, for example, the significance I demonstrated there... The treatment of the landscape here, the very timid treatment, he didn’t have the confidence. And here, look at how forceful this is. This is evolution; this is what I call evolution. There is evolution between this painting and that one, because he was just beginning. Here he shows fantastic confidence. |

|

|

The picture itself, the construction, color balance, composition, the surprising elements that he put into this composition. This wall above the column, it is a surrealist fact, a fact no one painted, I do not know any painter that painted a wall on top of a column. It is illogical. (...) I mean, there is painter in existence that has painted this. This was painted with depth, there’s contact with the so-called collective unconscious. Paul Klee attempted to achieve this kind of depth, but he always had to have “a ticket back”. Because he bought the ticket to go, but he bought the ticket back.

(...) And Emygdio didn’t, his was one way. (...) He had this incomparable depth. Nothing can compare (Mavignier, 1989). While the development in the treatment of painting is clear to Mavignier, this is offset by the fact that he is unable to clarify with equal precision what changed in Emygdio’s behavior: what improved in Emygdio was himself, his environment. We understood, we saw that people had a different kind of rapport with him when he was here. (...) I think that schizophrenics cannot give themselves to grand-scale affection... they are very economical in their expression of affection, of showing people... (...) that is my impression, because he rarely spoke, he was very shy (Mavignier, 1989). He was aware that the importance of Emygdio’s artwork surpassed his condition of insanity, once again, differentiating him from Raphael: Emygdio is an artist that doesn’t exist in museums. And besides, he did not come from Matisse, he had never seen Cézanne [emphasis added]. Even without seeing Cézanne (...) All of us, Brazilian painters, are influenced by Europe. He had no outside influence. This is really a unique situation. There is quality. For example, there is another quality from the point of view of painting, another aspect. They are all projections from inside. After he starts, on another picture, painting from nature, so, I mean, he put all of that world outside himself, and he started looking at nature. And then his fantasy begins to objectify in the painting. (...) I mean, it is a powerful picture that can’t be compared to any other Brazilian or international painter. (...) He did this completely on his own, nothing, there is nothing. That is the difference with Raphael (...) But we have qualified Raphael with those fabulous drawings because we have been influenced by Matisse, by Picasso [emphasis added], and we recognize in these drawings the best ones by Raphael. Perhaps the problem is our connection to Picasso, to Matisse, all that painting. Perhaps the great feature of Raphael is what he drew, that wasn’t worked over in painting (Mavignier, 1989). His observations lead us to reflect on how much our vision is conditioned by the knowledge that we have of art history. Matisse enabled him to understand the drawings of Raphael, while all the nurses saw were crazy markings. Putting together the fragments of his memories, we are able to track his conceptions of art and how these ideas determined his conduct as a teacher. Each of his patient-students merited differential treatment, which was dictated by the way Mavignier perceived their artistic inclinations. A master learns as he teaches. From close observation of the unknown that unfolded before his eyes came the recognition of the potentiality of the artwork still to be done. Creating conditions that would enable the visual tendencies of the patients to flourish in painting, drawing and other modes of artistic expression was the task that he generously committed himself to, above all because of the admiration he had for the artist he believed existed in each of those patients. He especially admired Emygdio’s work that he saw as distinct from everything that was produced under his supervision at the hospital: “that is the ‘miracle’ of Emygdio, he developed in parallel to the history of art, in an ever growing significance. Fantastic!” (Mavignier, 1989) He insists that an exhibit should be organized of Emygdio’s work that would do justice to the artist that he was, disregarding the fact that he was a schizophrenic: Well, deep down, in my opinion, there are no paintings of the insane, there is no insane art. There is art. There is art. It doesn’t matter. (...) Emygdio deserves it, also holding an exhibition of the painter Emygdio, without any other artist. Emygdio always had the bad luck of having exhibitions like “Emygdio and Raphael” and everything... The firms right off tell about the origins [from a psychiatric hospital]. They should hold an exhibition of Emygdio, just Emygdio, we would select a few things... When the psychiatrists look “Ah, that is very interesting...”, then take those out of the showing [that are interesting to psychiatry]. Separating what is viable is quite debatable. Discussions can go on and on... But the tactic is: let Emygdio occupy a very special exhibition for the history of art in Brazil (Mavignier, 1989). Raphael and Emygdio are no longer insane; in their paintings there are elements of great professional interest. (...) Mário Pedrosa included Emygdio in the Venice Biennial. There were one or two still lifes of Emygdio’s hanging there with no reference to schizophrenia, insanity, just as there is none for van Gogh, epileptic, when you see one of his pictures (Mavignier, 2005). Recognizing, respecting and enabling the other to develop his difference should be the first task of any teacher. That this artist Almir Mavignier, when he was just starting out as a teacher, was capable of welcoming the difference of a patient that had been confined for 23 years, considered a very deteriorated, chronic case, and still see him as an artist, helping him to develop his artwork, is worthy of praise. Many years later, as he remembered Mavignier’s performance in the studio, Fernando Diniz observed: |

|

|

“I was with Mr. Almir for a year, I was learning things. As time passed, he would be smiling, already. He liked his students very much: Isaac, Adelina, Carlos, Raphael, Brasil, Geraldo, Quintanilha, Alicia. He only liked those students. Then I arrived like: ‘no room for you’; but then he became friendly–‘come closer, young man. No one is the boss, this is public’, and he bought everything there. ‘Look, this is my studio here, come see my picture, everyone belongs. I win the greatest awards, you can win awards as well.’”

“What about you, did you like Mr. Almir?” “Well, just a smile means everything to me. If it hadn’t been for the monitor, there wouldn’t have been the organizations, they set everything up. Mr. Almir said that painting was a profession too, he was the teacher. At the end of the 1952, Mr. Almir went on a trip to be a professor at a university in Germany, a very good thing, too. He said: ‘I’m going, but I’ll be back to visit all of you every year’, and he came every year. Now, this year, he came again to see us. It seems like it was the same day back in 52.” (Mavignier, 1989). With these words, Fernando Diniz reveals his sense of belonging awarded by Mavignier’s gesture in sharing their work, offering painting to them as a profession that could be aspired by all. Diniz valued the quality of the way he welcomed everyone to the studio, but he also recognized the importance of how everything was set up: “just a smile means everything to me. If it hadn’t been for the monitor, there wouldn’t have been the organization, they set everything up.” The organization of the workplace revealed the didactic intention: the students, who in this case were patients allowed to work with autonomy and freedom. According to Jung: what works is not what the educator teaches through words, but that which he truly is. Every educator in the broadest sense of the term should ask himself again and anew the essential question: if he attempts to accomplish himself and in his life, in the best way possible, according to his conscience, everything that he teaches (Jung, 1981, p. 60). I consider it noteworthy that a patient such as Fernando was capable in those few words to present aspects that were the foundation of Mavignier’s “pedagogy” confirming that what the teacher truly is shines through the way he works. Mavignier the artist superimposed himself upon the teacher he was learning to become. When in 2005 he reflected upon his experiences at Engenho de Dentro, Almir recognized the importance of what he had learned in those early years and how that experience marked him as a teacher: Raphael and Adelina were professionals that were employees of the unknown [emphasis added]. This experience at Engenho de Dentro influenced me greatly, marked me as a teacher. My pedagogical conception is to enable young people to find their own personalities... (Mavignier, 2005). |