|

|

nove tendencije

|

|

Essay by Serge Lemoine from:

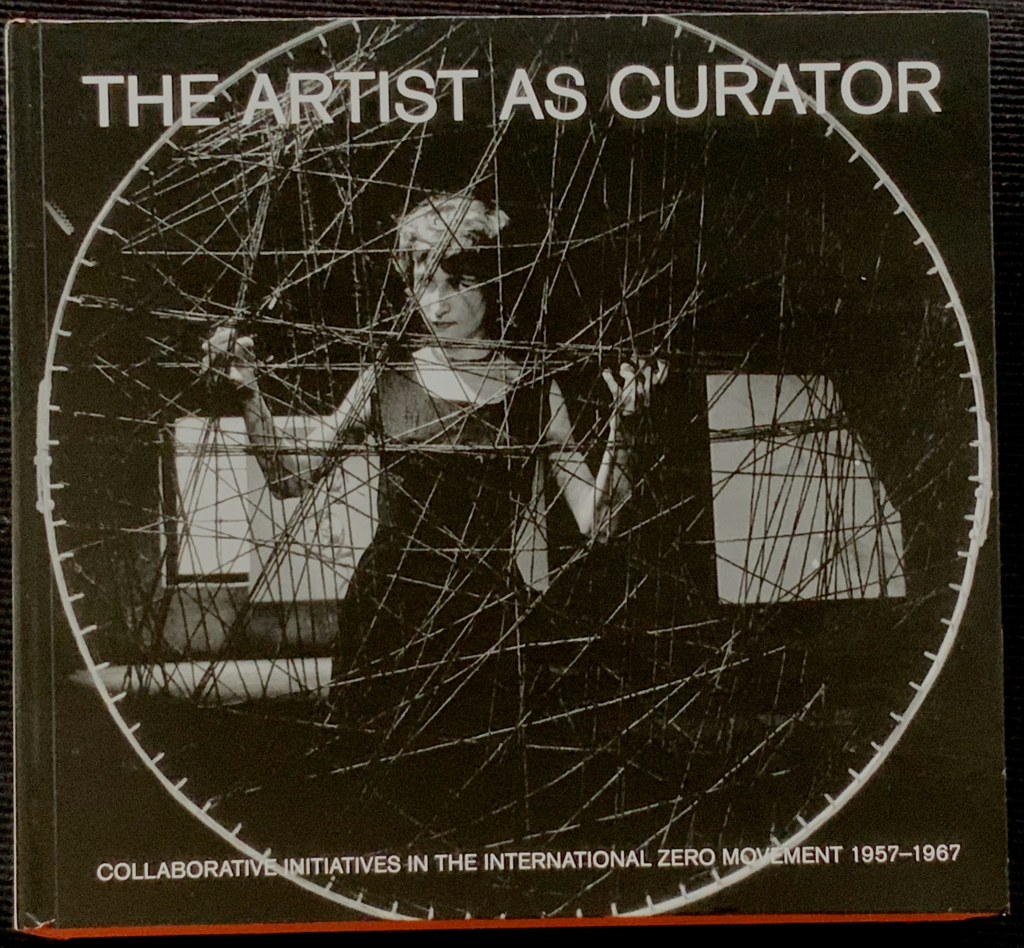

The Artist as Curator Collaborative initiatives in the international Zero Movement 1957-1967 von Tiziana Caianiello (Herausgeber), Mattijs Visser (Herausgeber), Dirk Porschmann (Redakteur) 2015 |

The Artist as CuratorNOVE TENDENCIJEEssay by Serge Lemoine

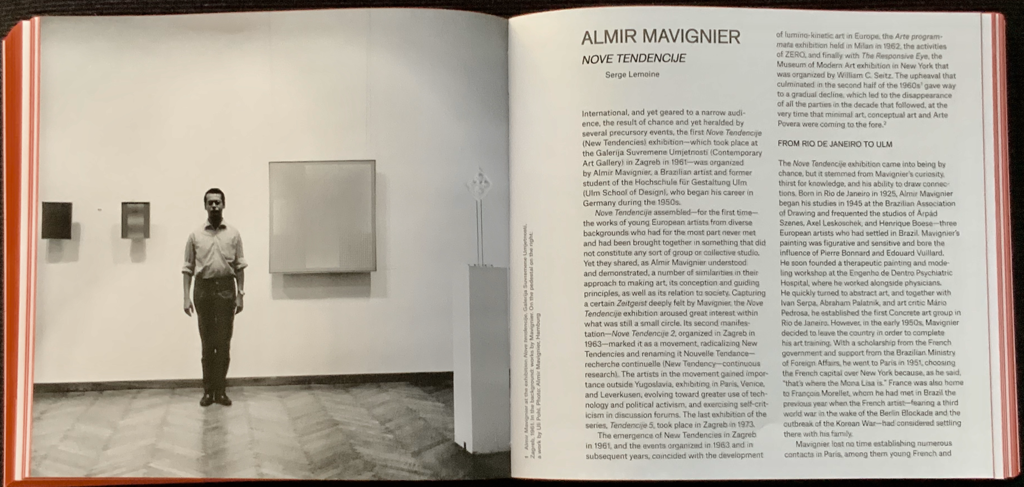

International, and yet geared to a narrow audience, the result of chance and yet heralded by several precursory events, the first Nove Tendencije (New Tendencies) exhibition - which took place at the Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti (Contemporary Art Gallery) in Zagreb in 1961 - was organized by Almir Mavignier, a Brazilian artist and former student of the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (Ulm School of Design), who began his career in Germany during the 1950s.

Nove Tendencije assembled - for the first time - the works of young European artists from diverse backgrounds who had for the most part never met and had been brought together in something that did not constitute any sort of group or collective studio. Yet they shared, as Almir Mavignier understood and demonstrated, a number of similarities in their approach to making art, its conception and guiding principles, as well as its relation to society. Capturing a certain Zeitgeist deeply felt by Mavignier, the Nove Tendencije exhibition aroused great interest within what was still a small circle. Its second manifestation - Nove Tendencije 2, organized in Zagreb in 1963 - marked it as a movement, radicalising New Tendencies and renaming it Nouvelle Tendance - recherche continuelle (New Tendency-continuous research). The artists in the movement gained importance outside Yugoslavia, exhibiting in Paris, Venice and Leverkusen, evolving toward greater use of technology and political activism, and exercising self-criticism in discussion forums. The last exhibition of the series, Tendencije 5, took place in Zagreb in 1973. The emergence of New Tendencies in Zagreb in 1961, and the events organized in 1963 and in subsequent years, coincided with the development of lumino-kinetic art in Europe, the Arte programmata exhibition held in Mitan in 1962, the activities of ZERO, and finally with The Responsive Eye, the Museum of Modern Art exhibition in New York that was organized by William C. Seitz. The upheaval that culminated in the second half of the 1960s1 gave way to a gradual decline, which led to the disappearance of all the parties in the decade that followed, at the very time that minimal art, conceptual art and Arte Povera were coming to the fore.2 FROM RIO DE JANEIRO TO ULM The Nove Tendencije exhibition came into being by chance, but it stemmed from Mavignier’s curiosity, thirst for knowledge, and his ability to draw connections. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1925, Almir Mavignier began his studies in 1945 at the Brazilian Association of Drawing and frequented the studios of Árpád Szenes, Axel Leskoschek, and Henrique Boese - three European artists who had settied in Brazil. Mavignier's painting was figurative and sensitive and bore the influence of Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard. He soon founded a therapeutic painting and modeling workshop at the Engenho de Dentro Psychiatric Hospital, where he worked alongside physicians. He quickly turned to abstract art, and together with Ivan Serpa, Abraham Palatnik, and art critic Mário Pedrosa, he established the first Concrete art group in Rio de Janeiro. However, in the early 1950s, Mavignier decided to leave the country in order to complete his art training. With a scholarship from the French government and support from the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he went to Paris in 1951, choosing the French capital over New York because, as he said, “that's where the Mona Lisa is.” France was also home to Frangois Morellet, whom he had met in Brazil the previous year when the French artist - fearing a third world war in the wake of the Berlin Blockade and the outbreak of the Korean War - had considered settling there with his family. Mavignier lost no time establishing numerous contacts in Paris, among them young French and foreign artists who were living in the capital at the time, such as Ellsworth Kelly, and those who were long-time residents, including Georges Vantongerloo. He also regularly visited the Morellet household in Clisson. Throughout 1952, he traveled up and down Italy on his scooter, visiting all the major art centers from Venice to Sicily. Over the course of his trip, he met Giorgio Morandi and also went to Zurich and Bern. He was introduced to Max Bill - who was busy with his plan of opening a school in Ulm modeled after the Bauhaus - as well as Richard-Paul Lohse, Camille Graeser, and Verena Loewensberg. In 1953, he visited the Lascaux cave, and traveled through Spain and Portugal, as well as Germany, where he discovered Munich, Stuttgart and Ulm. He came into contact with Karl Gerstner and Paul Talman in Basel, Marcel Wyss in Bern, and Andreas Christen in Zurich. In the autumn of that same year, Mavignier was accepted into the Visual Communication Program at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm, where he studied under Max Bill, Josef Albers, Johannes Itten, Walter Peterhans, Otl Aicher, and Max Bense. He began exhibiting his first Concrete paintings at the Salon des Nouvelles in Paris (1953) and at the Galerie 33 in Bern (1955). Mavignier returned to Italy before traveling to the south of Central Europe, to Greece in 1955, and then to Istanbul. In 1958, he graduated from the Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm. He showed his first "dot" paintings at the Municipal Museum in Ulm (1957) and at Studio F (1959) in the same town.3 Heinz Mack and Otto Piene invited Mavignier to participate in the seventh in the series of Abendausstellungen, or "evening exhibitions”, Das rote Bild, (The red picture), which took place in Düsseldorf in 1958. Atthe same time, he began working as a graphic designer, producing posters that breathed new life into the constructivist tradition of poster art. The following year proved to be a watershed in his development: it was in 1959 that he participated in the premonitorily titled exhibition Stringenz: Nuove Tendenze Tedesche (Stringency: new German tendencies) at the Galleria Pagani del Grattaciel in Milan, along with seven German artists.4 It was here that he met Enrico Castellani, Piero Manzoni and Antonio Calderara - who was to become a close friend - as well as the future members of Gruppo N in Padua.5 He was introduced to Herbert Oehm, Gerhard von Graevenitz, Rudolf Kämmer, Gotthard Müller, Uli Pohl, and Walter Zehringer, adding to his network of contacts in Munich. FROM ULM TO ZAGREB Almir Mavignier's enthusiasm and curiosity, his taste for new discoveries, his interpersonal skills and his interest in the latest trends, together with his political activism, made him an uncommon personality in the art world. There was no stopping him: In 1960, he exhibited his works in Leverkusen,6 on several occasions at the Galleria Azimut in Milan, and in Zurich, Konkrete Kunst (Concrete art) exhibition, organized by Max Bill, a range of shows that demonstrate the extent of the recognition he was enjoying. In the fall, he visited the Venice Biennale, and on his way to Egypt, he passed through Yugoslavia, before boarding a Soviet ship in Piraeus bound for Alexandria. He stopped in Zagreb, and on the recommendation of a friend from Ulm who was an art collector, he contacted the Croatian artist Frano Simunovie, who wasted no time introducing him to Ivan Picelj, a young painter with constructivist leanings who was also an accomplished graphic designer, and Matko Meštrović, an art critic who was committed to political causes without being dogmatic. Mavignier was immediately invited to take part in a debate on the Venice Biennale, where he shared his thoughts on the state of art at that time and revealed his interest in Piero Dorazio, the only painter in Venice who was, in his view, creating something new. What emerged from this discussion was the idea of an exhibition in Zagreb, which would feature proposals made by the young artists who had caught Mavignier’s attention. Božo Bek, the director of the Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti Zagreb, was quick to invite Mavignier, who was in Ulm at the time, to organize the exhibition that would be shown in his gallery the following year. Numerous letters were exchanged between Matko Meštrović, Bek and Mavignier in order to establish the list of whom to invite, and the exhibition was on view from August 3 to September 14, 1961. Mavignier had selected twenty-nine arlists,7 the majority of whom were Italian, German, Swiss, French, and Croatian. Some were already labeled kinetic, others espoused constructivist art, a few were aligned with Dada, and many were protagonists of the ZERO movement.8 Mavignier met and corresponded with all of them, as evidenced by his letter to Heinz Mack in December 1960,9 with the exception of Julio Le Parc, who had been recommended by Frangois Moreltet's wife, Danielle. All the artists accepted Bek's invitation; Piero Manzoni was the only one who expressed reservations - not wanting to appear in a context that did not correspond to his own approach - before ultimately accepting. ZAGREB, YUGOSLAVIA The eighty-three artworks10 exhibited in the rooms of the Kulmer Palace-where the museum had been housed on the ground floor since 1954 - shared many common characteristics: an absence of composition, the repetition of identical elements or units, the prominence of the line, an absence of limits, an open form, achromia, a basic structure, binary organization, and the use of new media and anonymous craftsmanship, or even industrial forms of production. A constant began to emerge as the artworks of Gruppo N were projected into the viewer's space. The works were shown in a suite of rooms occupying 2,691 square feet (820 square metres) in a vaulted gallery. The hanging was simple, uncluttered, and arranged in a single row, in order to highlight the works on the white walls. Some pieces sat on pedestals (Uli Pohl), others were presented horizontally (Paul Talman), and many were completely detached from the wall. The exhibition was entitled Nove Tendencije in reference to the 1959 Milan exhibition featuring German art (Stringenz: Nuove Tendenze Tedesche), though Avant-garde 1961, Avant-garde, and Konkrete Kunst had also been considered as suitable titles. Ivan Picelj designed the poster as well as the exhibition catalog, which included essays by Matko Meštrović and art historian Radoslav Putar. The originality of the concept, the visual innnvation of the mayority of the works, and the radical nature of their intention contributed to the immediate and undeniable success of Nove Tendencye. Yet it fell within the scope of exhibitions organized in 1960 by Enrico Castellani and Piero Manzoni at the Galleria Azimut in Milan, those organized by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene in Düsseldorf, and the Konkrete Kunst (Concrete art) exhibition shown by Max Bill in Zurich - also in 1960. Mavıgnier’s judgement and his ability to interpret the spırit of the times enabled him to establish connections between the different exhibitions, to find commonalities between certain artists and bring them together in a way that highlighted these new tendencies. At a time when art was defined by an exacerbated sensitivity combined with unbridled expression, one witnessed the rejection of composition, the use of neutral, repetitive and interchangeable elements, an impersonal technique, and the will - which brought intelligence to the creation - to further involve the viewer by influencing his/her perception. That the exhibition was held in Zagreb - that is to say in Yugoslavia, a communist country where the principles of "socialist realism” were supposed to be applied - might seem paradoxical, were it not for the freedom of artistic expression that prevailed at that time in the socalled "non-aligned“ country. Yugoslavia was also home to the group EXAT 51.11 of which Ivan Picelj was a member, and Gorgona,12 a group that included Matko Meštrović and Radoslav Putar. As we have seen, this exhibition was a product of happenstance.13 Yet the events that followed would give ample argument to Mavignier’s ideas. In 1963, a second Nove Tendencije exhibition was held in Zagreb, which confirmed those trends, yet also radicalized them aesthetically and ideologicaliy.14 Almir Mavignier no longer had a say in the matter. Notes

Essay by Serge Lemoine from:

The Artist as Curator Collaborative initiatives in the international Zero Movement 957-1967 von Tiziana Caianiello (Herausgeber), Mattijs Visser (Herausgeber), Dirk Porschmann (Redakteur); 2015, ZERO foundation, Düsseldorf |

neue tendenzen aide-mémoireErinnerungs Memo von Almir Mavignier:

FREUNDSCHAFT KOLLEGIALITÄT SOLIDARITÄT

sind die spuren des zeitgeistes der 50er/60er jahre, welcher künstler miteinander verbunden hat: 1950 rio de janeiro françois morellet trifft almir mavignier, 1951 paris/cholet mavignier trifft morellet und joel stein, 1953/54 ulm mavignier trifft martin krampen und adolf zillmann, 1954, rom krampen und mavignier treffen piero dorazio 1954/58 schweiz mavignier trifft: marcel wyss in bern, karl gerstner und paul talmann in basel, andreas christen in zürich 1958 düsseldorf mack & piene laden mavignier zur abendausstellung, 1959 mailand klaus jürgen-fischer organisiert die ausstellung „STRINGENZ - nuove tendenze tedesche“, mit: busse, holweck, fischer, kricke, mack, mavignier, sellung und vorberg in der galleria pagani del grattacielo 1959 mailand mavignier trifft enrico castellani, piero manzoni und antonio calderara, castellani und manzoni machen mavignier in padua mit den mitgliedern der gruppo enne: biasi, chiggio, costa, landi und massironi bekannt 1959 münchen mavignier besucht herbert oehm in der kunstakademie, er trifft dort: gerhard von graevenitz, rudolf kämmer, gotthard müller, uli pohl und walter zehringer 1960 ZAGREB mavignier ist mit dem auto von ulm über venedig, jugoslawien, griechenland und per schiff nach alexandria unterwegs. ÄGYPTEN WAR IM KOPF zagreb auf der landkarte, er übernachtet dort. ein ulmer sammler bat ihn, den maler frano simunovic zu besuchen. simunovic stellt ihn ivan picelj und matko mestrovic vor. beide haben mavignier zu einer podiumsdiskussion über die biennale von venedig 1960 mitgenommen.vgefragt wurde über neue richtungen, die bei der biennale zu beobachten waren. mavignier antwortet "keine", weil die biennale bereits bekannte künstler zeigt. wer neue richtungen erfahren will muss in den ateliers suchen. mavignier schlägt eine ausstellung vor um unbekannte: JUNGE KÜNSTLER IN ZAGREB BEKANNT ZU MACHEN und setzt seine reise nach ägypten fort. zurück in ulm erfährt er aus zagreb, daß sein ausstellungsvorschlag realisiert werden sollte. eine fleissige korrespondenz zwischen mestrovic und mavignier folgt. einige briefe von bozo bek. mavignier wird gebeten, namen und adressen der künstler zu geben: marc adrian, alberto biasi, enrico castellani, enno chiggio, andreas christen, giovanni antonio costa, piero dorazio, karl gerstner, gerhard von graevenitz, rudolf kämmer, eduardo landi, julio le parc, heinz mack, piero manzoni, manfredo massironi, almir mavignier, françois morellet, gotthard müller, herbert oehm, otto piene, uli pohl, joel stein, paul talman, marcel wyss und walter zehringer sind die künstler, die vorgeschlagen werden. künstler aus brasilien wurden aus räumlichen gründen nicht eingeschlossen. mavignier schlug vor, daß alle künstler die gleiche anzahl von arbeiten schicken - mindestens drei - welche JURY-FREI in der ausstellung gezeigt werden sollten. arbeiten von ivan picelj und julije knifer aus zagreb wurden von seiten des museums der mavignier-auswahl hinzugefügt. als titel der ausstellung wurde NEUE TENDENZEN aus dem untertitel der mailänder STRINGENZ heraus, von mavignier vorgeschlagen. mavignier wurde nach zagreb eingeladen, um die ausstellung zu gestalten. ÜBERRASCHUNG DER AUSSTELLUNG: TAFELN UND OBJEKTE, die weder bildern noch plastiken entsprachen. die verwandtschaft der arbeiten von künstlern, die sich noch nicht kannten, bestärkt der eindruck, eine kunstbewegung zu vermuten. almir mavignier januar 2013 |