|

|

Marks and memories:

Almir Mavignier and the Painting Studio at Engenho de Dentro Lucia Reily, José Otávio Pompeu e Silva and collaborators Research behind the scenes

Lucia Reily and Rosa Cristina Maria de Carvalho

|

“It is very interesting, that things don’t last very long; they go away. Everyone feels nostalgia. Why did it finish? Why is it over? Yes, it’s over. The best thing that remained was the memory.” |

|

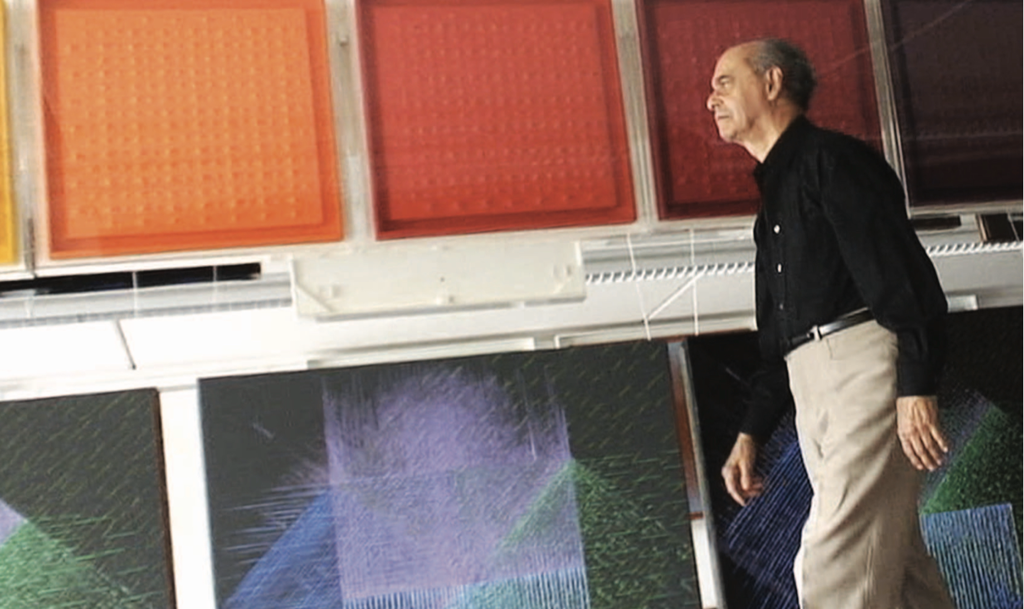

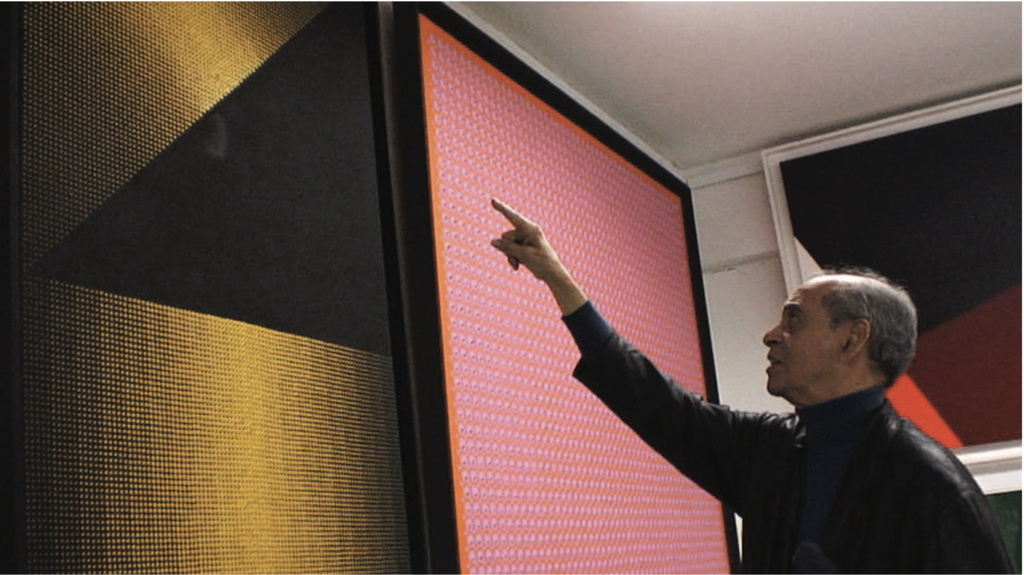

Almir Mavignier had a central role in establishing the painting studio at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional in 1946, where hundreds of drawings, paintings and sculptures were produced, that came to make up part of the collection of the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente (MII). However, because he moved to Europe in 1951 and has resided in Germany for almost sixty years, his version of the history of the early years of the studio where patients interned in a psychiatric hospital in the Engenho de Dentro neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro was given an opportunity for artistic expression has become submerged under layers of many other versions of the story. The story that prevailed was the one reported by Nise da Silveira (1906-1999), because she was the one responsible for promoting the consolidation of the artwork during the many years she dedicated to analyzing the material produced at the painting studio, for promoting awareness of the material and for being the caretaker of this valuable collection.

We do not regard the reports that attempt to describe and give details on how everything began to be necessarily dissonant. To us, all stories deserve to be heard, because each one distinctively illuminates relevant issues and details that instigate our desire to understand the facts more fully, since the professional fields of each actor in this play influence the performance of those involved in the activities proposed by the painting studio. According to Silveira (1966), Mavignier’s era at the painting studio dated from September 9, 1946 to November, 1951, only six short years. For a project in its early phase, six years represent a period of great importance. In this case, the work done by Mavignier, a burgeoning visual artist working with patients residing in a psychiatric hospital, ensured the necessary aesthetic ambience of the proposal. Even though he worked under the supervision of Nise da Silveira, Mavignier was able to bring to the studio his perspective as a visual artist. He established the tone in the way he organized the daily workings at the studio, a legacy we can still make out in the discourse produced to this day about the painting studio. This experience was essential to his process of becoming a visual artist and art teacher. Although Mavignier only worked at the studio for six years, he participated in the history of the painting studio on later occasions, thanks to the contact he maintained with Nise da Silveira. He participated as curator, as well as photographer of exhibits of Engenho de Dentro artists in expositions held at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional in December of 1946; at the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro in February and March, 1947; and at the headquarters of the Associação Brasileira de Imprensa also in March of the same year. As the production developed and captivated the interest of art critics, museum professionals, as well as visual artists, other doors were opened. In 1949, an emblematic exhibition was held at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo–“Nine Artists from Engenho de Dentro”. That same year, the artwork was shown again in Rio de Janeiro at the Municipal Chambers. In Europe, Almir Mavignier responded to Silveira’s invitation to mount an exhibit called “Schizophrenia in Images” at the II World Congress of Psychiatry to be held in Zurich from September 1 to 7, 1957. Part of the collection went on to the Paris City Council. Finally, in 1994, Mavignier prepared an exhibit with part of the MII collection at the 46th Book Fair in Frankfurt. |

|

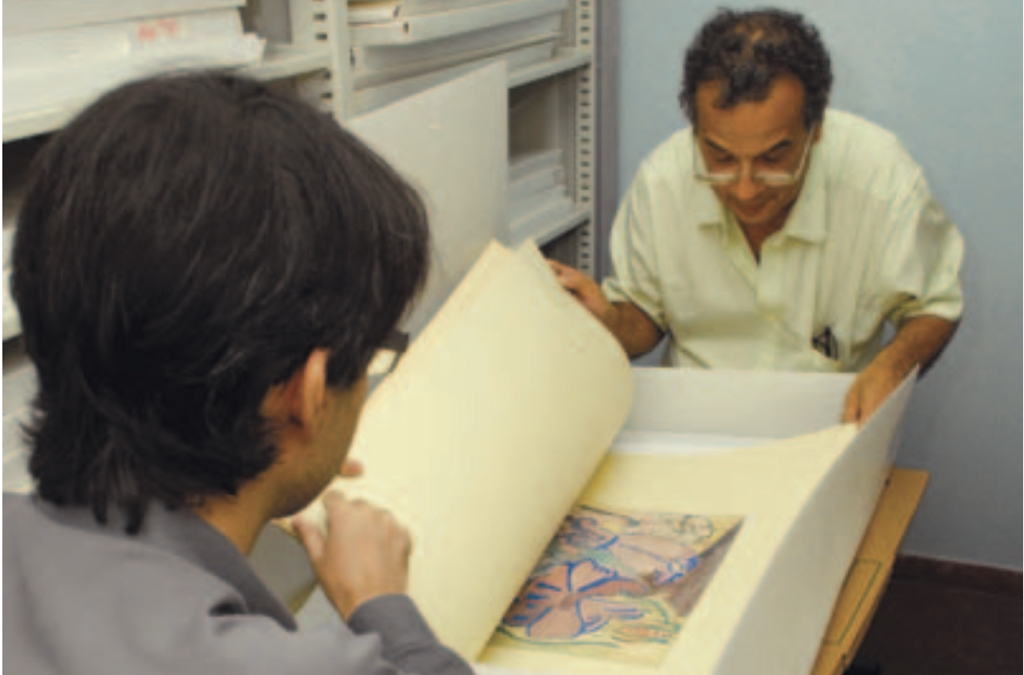

Besides participating in the organization and curatorial management of national and international showings of the works produced at the painting studio, Mavignier also shared his knowledge of various historical aspects on what happened behind the scenes at the studio between 1946 and 1951. He accepted the invitation of the MII’s staff in 1989 in order to help organize the collection. On another occasion, when the Mostra do Redescobrimento was underway in 2000 in São Paulo, he was consulted once again and produced a text that was published in the Imagens do Inconsciente bilingual catalogue, where he singled-out Arthur Amora’s works (Mavignier, 2000.)

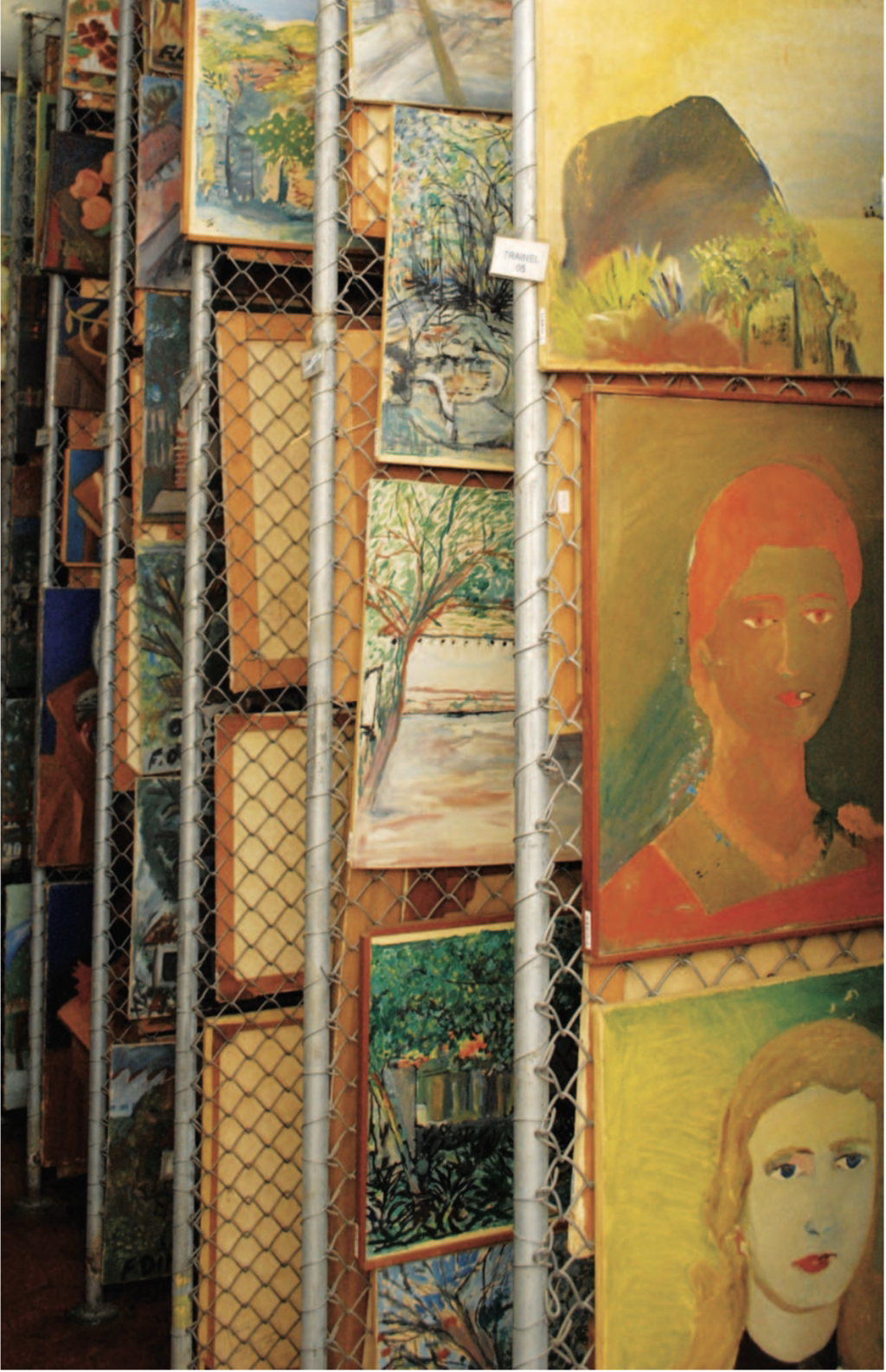

Due to this legacy, the museum acknowledges the important role played by Mavignier when mentioning his name in publications that recover the early years beginning in 1946. The MII played a major role during our research project, because it houses the entire collection of drawings, paintings and sculptures produced over the years at the studio in the Occupational Therapeutics and Rehabilitation Ward, including those done under Mavignier’s supervision. The MII staff, especially the director Luiz Carlos Mello, provided excellent research conditions in the collection, besides indicating other contacts and investigative possibilities when the information we required could not be found at the museum. Besides the artistic production, of which part has been inventoried by the Instituto de Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (IPHAN), the collection also houses Nise da Silveira’s personal library. There one can find a collection of newspaper and magazine articles with news items related to the activities that took place–such as exhibits, conferences and other events–all of which were preserved by the psychiatrist along with books, and more recently, theses and dissertations. There is also a collection of films, including invaluable documentation of practices and ways of thinking about art and mental health. Besides these materials, there are photographs that helped us compose the scenario where Mavignier’s narrative about his work at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional unfolded. The memory and the voice of the artist

The fact that Mavignier had lived in Europe for several decades, except for a few sporadic visits to Brazil to take care of personal affairs or for events such as art exhibits and the production of catalogues, contributed to the preservation of a pristine memory of distant events. Understanding memory as a psychic process of dynamic reconstruction of events, this study, which is organized according to Almir Mavignier’s remembrances, required us to look at the artist’s later experiences–mainly the position he took as he reencountered the material in the MII collection and the people involved in the Engenho de Dentro activities. At one point, when questioned about his artistic trajectory, Mavignier himself recognized how transient situations can be and how experiences, affect and memory pass away: “It is very interesting, that things don’t last very long; they go away. Everyone feels nostalgia. Why did it finish? Why is it over? Yes, it’s over. The best thing that remained was the memory.” (Concrete Memories, 2006). Considering experience to be an understanding of value on an individual level, steeped in personal sensibility and constructed on a basis of uncertainties (Larrosa, 2002), and conscious that such knowledge is a source for memory, we attempted to construct a narrative meant to accentuate the sensibility revealed in the recorded interviews. That is why we began our search and defined the treatment intended by looking first at the transcripts of the interviews. When Pompeu e Silva began his investigation on Almir Mavignier’s role in the painting and modeling studio at the Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional in 2003, he uncovered a few video recordings that contained relevant information on the way the studio experience took place during the Mavignier era (from 1946 to 1951):

Between 2005 and 2007, Mavignier gave various interviews that were filmed or audio recorded several times on his history as a concrete artist and about his work at Engenho de Dentro from 1946 to 1951. The motivation for the recordings were various; some interviews focused on the works of the artist-patients, as was the case of the interview collected by Patrícia Rohleder Filipp (Mavignier, 2006) and Maria Cristina Amendoeira (Mavignier, 2005). On the other hand, the theme of Roberto Berliner’s interview in 2009 featured Nise da Silveira, while Nina Galanternick and Glaucia Villas Bôas (Concrete Memories, 2006) were looking into the historical role Almir Mavignier played as a concrete artist. Besides the recordings taped in audio and filmed in audio and video, Pompeu e Silva collected information directly from Mavignier primarily by email, and sometimes over the telephone to clarify uncertainties. In 2006, he mediated Patrícia Filipp’s contact with the artist, and the result was an extensive and detailed interview with Mavignier who was 81 years at the time. In the various interviews granted, Mavignier talks clearly about what happened in days gone by. Provoked by his interviewer’s questions, and by images and commentaries, he has been quite capable of restoring the uniquely relevant collective history for those who study and work in the field of artistic production in the context of mental health. When we have before us the transcripts of the various interviews that Mavignier granted since 1989 on the first years of the painting studio, it is possible to see that some instances of his discourse have crystallized into enunciations that are sometimes fixed, sometimes variable. That is in the nature of oral history which values the meanings that facts represent to people as much as the objective data. According to Becker (1998), an oral deposition constituted after an event always suffers from inconveniences such as: It can recover remembrances that are involuntarily misrepresentations, memories transformed because of later events, memories superimposed, memories deliberately transformed so as to coincide with what is conceived many years later, memories transformed simply in order to justify positions and later attitudes (p. 28). It is of the nature of the narrator to weave a cohesive cloak onto which parts of the story can anchor themselves. Even though dates, names of people or places may escape us, we are still capable of remembering events that happened from a thread that holds together a sequence of occurrences. In the transcripts that were gathered together, sometimes the investigation itself instigated Mavignier to revisit specific aspects of his experience as a fresh look at the past. Mavignier’s interviews were not our only sources during this research project, though they did function as scaffolding for putting together the texts of collective narrative history that make up this book. Newspaper articles, literature of various kinds, catalogues, written correspondence and documents of different kinds were consulted in order to confirm information and clarify divergent opinions. |

|

The oral history method enables the researcher to establish deeper relations with those that grant the interviews, but it also presupposes the data obtained by means of the oral source will be articulated with other kinds of documental sources and pictographic records of various kinds in order to construct a version of cultural history. According to Lozano (1998), this kind of research implies theoretical reflection and fieldwork; greater personal involvement with the subjects being studied; a process of constitution of a source and a process of production of scientific knowledge, i.e., a process that enables the researcher to transform himself into what he has always meant to become, a historian (p. 24).

So, we are not overly concerned that the enunciations from different moments in time spoken to various researchers might present discrepancies. We are not looking for one objective truth, but rather, we seek to establish a complex and rich range made up of intricately woven fibers. At any rate, Mavignier’s voice brings a fresh perspective on the work that was accomplished between 1946 and 1951. Some incidents have already been mentioned by Nise da Silveira who was a consummate writer and wrote many papers on the production of the Engenho de Dentro artists; nevertheless, the daily activities behind the scenes at the painting studio were the domain of Mavignier, whose voice we have set out to highlight in this project. It should be noted that he himself has already promoted the publication of his story about the painting studio in several exhibit catalogues, albeit in short version. Almir Mavignier was a visual artist just starting his career when everything began. He was developing his personal poetics both in the Painting Studio at Engenho de Dentro and in the classes he was taking with Arpad Szenes, followed by Axl Leskoschek and Heinrich Boëse (or Henrique Boese as he was known in Brazil.) The studio played an important role in helping him define his identity–in the interviews, he recognizes and values the meaning of this experience for his burgeoning career. The support he received from Nise da Silveira was essential when he first went to Europe, and was still employed by the state of Rio de Janeiro, trying to figure out if he should go back home or stay on for another season. Mavignier: I didn’t leave Engenho de Dentro. I got a scholarship to study in France. My studies were compatible with my situation as a monitor working as a painter. If I had a scholarship to study in France, that was compatible. Not with my level as a government employee, but my level as a monitor. I mean a monitor that has been upgraded. So I left with the scholarship. I spent six months, Paris, Italy, and I extended my scholarship (...) and that is where Nise’s great qualities showed through–she tolerated that–not only did she tolerate it, but she sustained it. She didn’t have any bureaucratic troubles (Mavignier, 2006). Public functionary, artisan, studio monitor, exhibit curator, therapist, visual artist–among the many positions he held, Mavignier defined his place in the daily practice of the studio. In some documents, he seems to have assimilated designations that were attributed to him by others who confused what he was doing with therapy. The Fundação Nacional de Artes (Funarte) in Rio de Janeiro holds a folder of documents on Almir Mavignier, among which there is a letter he sent to Roberto Pontual dated September 14 , 1976, in which the artist set out a chronological list of biographical items. He defined his professional standing at Engenho de Dentro in the following lines: 1947/1951–worked as therapist [emphasis added] at the centro psiquiátrico nacional at engenho de dentro, founding the painting and modeling studios. In another document that is part of this file, Mavignier recorded names of people that were significant in orienting his trajectory. In this instance he also calls himself a therapist: 1947–dr. nise da silveira psychiatrist and director of the praxitherapy services at the centro psiquiátrico nacional at engenho de dentro, with whom I worked as therapist [emphasis added] of that service. As he reflected upon his work, he realized that he had played another role. His interest in the production of the patients was related to the language of art; his contribution had to do with bringing to light the aesthetic potentialities of the people that participated in the studio. Promoting treatment through expressive therapeutics and interpreting the patients’ history using artistic productions as an instrument was Nise da Silveira’s job. Mavignier: Nise had psychiatric interests; naturally, because she was a psychiatrist. My interest was artistic. And I was interested in discovering the artists there in the studio, but it was a personal interest. With such an interest, I really couldn’t do anything there because it wasn’t an art school. It was a therapeutic occupation (Mavignier, 2006). Still, his work with the patients was actually therapeutic, as he enabled them to have a place where they could be acknowledged and where the expressions of each participant of the painting studio was valued, as we shall see in Chapter 5, by Ana Angélica Albano. |

|

Mavignier told his interviewer Patrícia Filipp that he saw Pompeu e Silva as a true detective, who uncovered a story no one knew anything about.

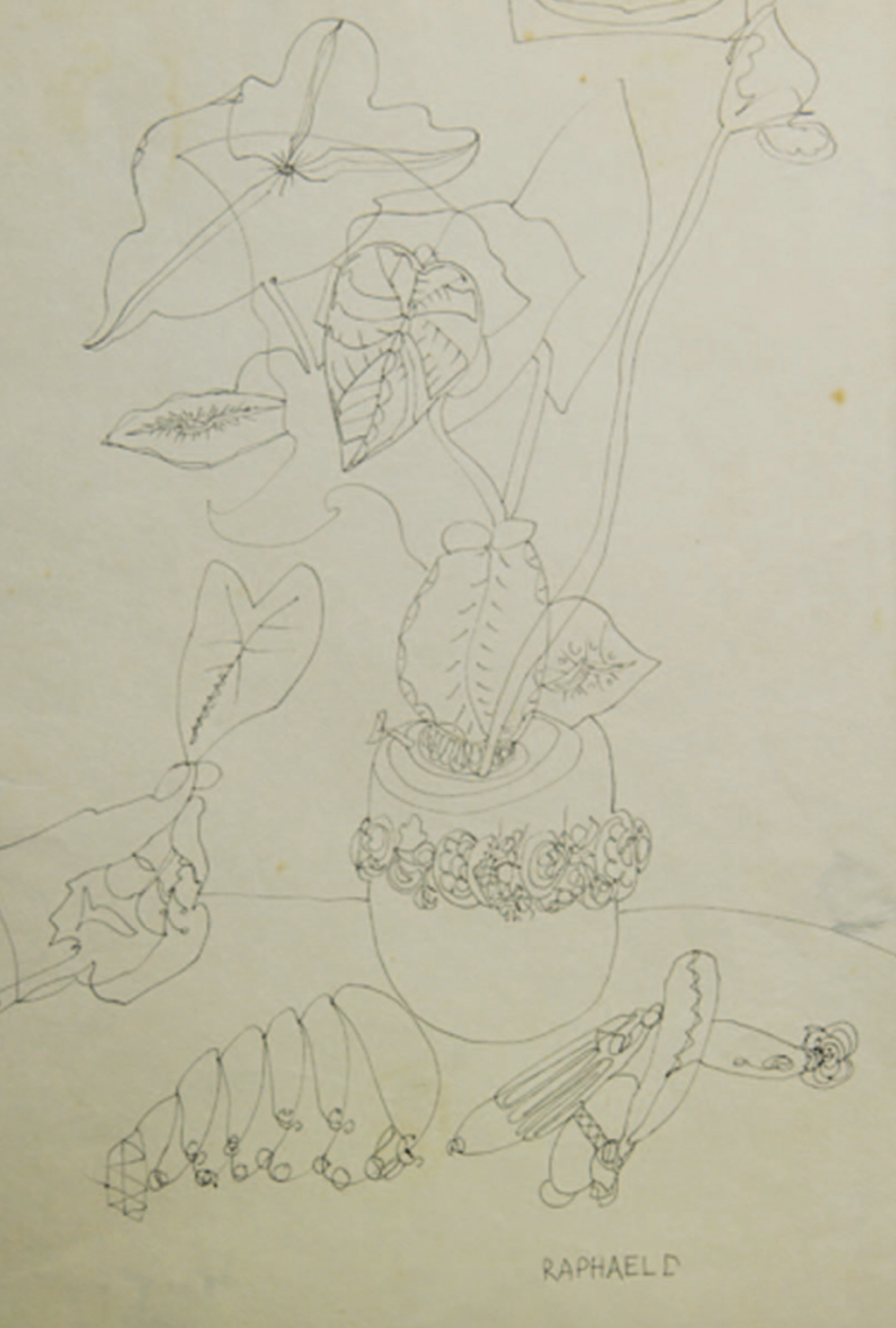

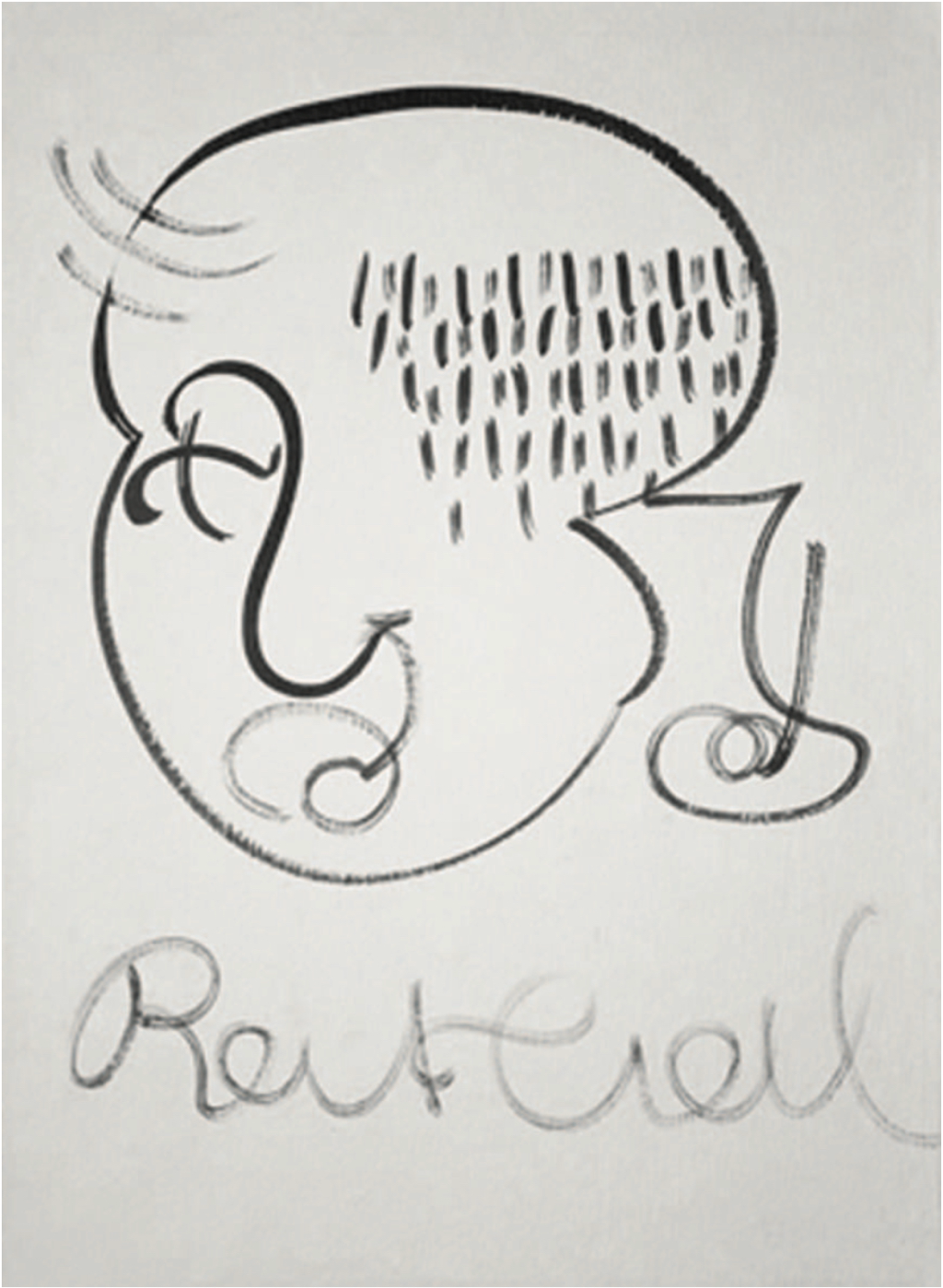

Pompeu found me out, right? I told you that, he found me because of the interviews, like a detective, he found me. He discovered my role and I am very grateful for that. So he is going to write a book, and I suggested that the book could be in great part our correspondence. With emails, lots of emails. And the last time he asked me many questions (Mavignier, 2006). When Patrícia Filipp interviewed him, Mavignier cautioned her that he was aware of information that only those who had witnessed the production at the studio knew about. For example, he told her of an episode in which one of the participants of the studio, Raphael, had been drawing a Christ figure, and at the bottom of the page he drew a fish, an important Christian symbol. And something else no one knows. Pay attention, because if I should die tomorrow, no one will know this. For example, those paintings by Raphael he did using large brushes. The strong brush strokes are where he started. Because he only wet the brush once. So that the weaker part is where he finished. Who knows that? No one. They are letting me die without listening to me [emphasis added] (Mavignier, 2006). Mavignier was very generous in his interviews, concerned about making sure that hidden meanings of the drawings of the collection were uncovered. As he turned the pages of the Frankfurt catalogue for Patrícia, he explained what happened during the still-life drawing sessions at the painting studio, with special emphasis on Raphael’s unique poetic process. I would put the objects there. Paint what you see, do what you see. That is, I was still setting up, I was setting up the fruit and he drew my hand. No one knows that. One day I will be gone, and no one knows (Mavignier, 2006). |

|

|

An emblematic example can be seen in Raphael’s drawing of a plant arrangement. At the top of the page, there is a figure that Mavignier explained.

See here, for example: “here, look Raphael, how pretty.” With my hand, I held the leaf. He did it immediately, in seconds, my hand holding the leaf. And this (pointing) was at the back; here it is cut off because it was the top of the paper. It wasn’t on the table. It was the electricity box. In old houses, there is a light switch box for paying the light bill (Mavignier, 2006). It is clear that recovering information on how the work at the studio was developed was important to Mavignier. At the same time, he understood that José Otávio Pompeu e Silvas’s thesis was not his own deposition, but rather a representation constructed by the researcher. He would like to tell his own story about the painting studio in a richly illustrated and magnificently designed catalogue. He told us over the telephone that one day he plans to do this. Mavignier is right. Someone who tells another person’s story leaves their own marks in the way they connect the facts, in their interpretations and in how they select some emblematic images whilst leaving others out. Although we listened attentively to Mavignier’s recordings, we have chosen certain major elements that we considered to be emblematic in the way he operated as a teacher-artist. Our intent is to show how the artists’ knowledge can make a difference in the artistic production at the studio and in art teaching. As often happens when people are involved in collective processes, tensions arise over time, but we are not to judge or take sides. Hurt feelings and dissatisfaction are part of the human makeup and natural to the production movement and longing for recognition. We must note, nevertheless, that no matter how meaningful the first years at the Engenho de Dentro painting studio were, Mavignier doesn’t attempt to hide the fact that at that time, he had to juggle his work at the hospital with his goal to develop his career as an artist. That was his main priority. His work at the painting studio was intense, demanding total immersion, but was also quite stressful. As a result, he realized after a few years that it was time to look for another way of pursuing his career as an artist. At the end of five years I was exhausted. I couldn’t do it anymore. No. I was their slave. And with great joy something stupendous happened, from the French government and I was free of all that; I left it to their destiny. So, in 51, I came to Paris (Concrete Memories, 2006). Even though he went off to Europe, he recognized how much the experiences he had been part of at Engenho de Dentro had meant to the development of his poetics and understanding sources of internal creativity as well as the experimental character of pictorial construction. The work at the painting studio was also important in preparing him as an educator–where he learned to encourage students to look for content for creation from within their own personalities, free from passing fads. We do hope that Mavignier will feel comfortable with his own words on these pages and we also look forward to seeing his own story published according to his own design. Research at the university as a locus for student development From the perspective of the university’s mission, the aim of this project was to involve the academic community, including faculty researchers, graduate and undergraduate students and other contributors in a project of great historical and social relevance, in order to promote research and production encompassing several domains (art, health and education). This collective effort aims to contribute to the recovery of data that has been scattered throughout various places, to acknowledge the artist’s role in multidisciplinary teams offering new proposals of out-patient psychiatric treatment. The aim is to help understand the uniqueness of Mavignier’s work, drawing attention to the importance of a visual artist in a therapeutic studio. The possibility of digitalizing, preserving, cataloguing and promoting awareness of the work from this specific moment in history will help to prevent the loss or destruction of documents or the dispersal or fragmentation of the collection that is so important to Brazilian art. Preserving this story is relevant because the visual art work of psychiatric patients continues to generate interest from art students. Their interest derives from being enchanted by the unique visual compositions themselves, as well as from contact with such work in museums, schools and art workshops that have broadened teaching opportunities for artists working in settings of social inclusion. When considering student preparation at the university level, where various professionals at different stages of development come together, there is a unique opportunity for exchanging academic experiences where beginner students become aware of the responsibilities involved in a research project. Currently, in higher education, the preparation for research begins early on. Shortly after enrolling, undergraduate students may submit student projects in order to gain “beginner” research scholarships. This was the case for several participants on our team, to the extent that when the first group of young researchers arrived at the Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente in order to collect data and images for the first phase of the study, they were met with skepticism. How could such young students be capable of undertaking the complex tasks required to achieve the objectives of the project? Like them, Almir Mavignier was young and very audacious. His early history shows a young artist, just 21 years old in 1946, still unknown in art circles, attempting to stake out his own creative territory. While he was setting up the Painting Studio at Engenho de Dentro, he was also making his first professional incursions in the field of visual arts. He had defined his career choice, but his course was just beginning. This young man moved in cultural spaces in Rio de Janeiro, meeting art critics and other intellectuals, getting to know new artists at a time when the art scenario was in transition. He brought to the studio a great source of energy and capacity for innovation. Invited by Mavignier, painting students visited the hospital studio and set into motion a stage for dialogue between the expressiveness of people usually deemed incapable and a generation of emerging artists in search for a new visual composition. Right at the start, he already believed the work deserved to be exhibited. The venues he sought were not small rooms in philanthropic facilities, but rather prominent spaces within the artistic and intellectual scenario of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, such as the facilities of the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro and the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAMSP), which were representative venues for promoting innovations and forming public opinion. |

|

The student researchers began the survey by generally mapping the location of material, searching for documents in collections housed in museums and heritage centers in São Paulo (Museu de Arte de São Paulo−MASP, Museu de Arte Moderna−MAM-SP, Museu de Arte Contemporânea de São Paulo−MAC-SP, and the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo) and in Rio de Janeiro (Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, Museu de Arte Modern Arte do Rio de Janeiro–MAM-RJ, Museu de Arte Contemporânea–Niterói, etc.).

The Mário Pedrosa Collection at the Biblioteca Nacional in Rio de Janeiro was investigated with emphasis on manuscripts, iconography and newspaper articles. Newspaper and magazine articles were examined to uncover material about Almir Mavignier in books, catalogues and other periodicals. Numerous documents were studied from the iconography collection, both at the library and in the MII collection, with the help of the team that digitalizes relevant material. |

|

|

The MII director, Luiz Carlos Mello, granted interviews and undertook the task of digging out old photographs from the period when Almir Mavignier was active at the painting studio. He authorized the reproduction of images that were essential to understanding the relationships between artists and patients and how the first exhibits were organized. Eurípedes G. da Cruz Junior helped the young researchers look through the interviews and documentary films that were kept at the MII. The museum staff did a magnificent job preserving the material that is so important for reconstructing the history that this book entails to report. Without the tremendous investment in the creation of collections of works and the organization of filmed documents and articles from newspapers and other periodicals, research projects such as this would not be feasible.

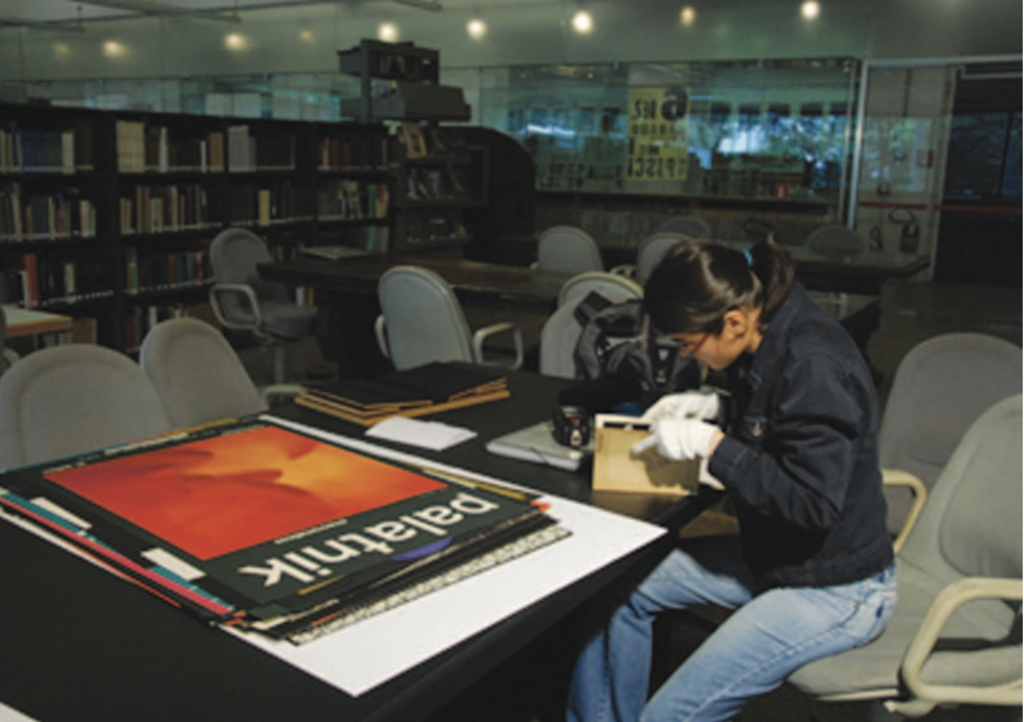

The collection of drawings and paintings is organized in portfolios identified according to authorship or themes that are dear to Jungian theory. At first the portfolios were separated by Almir Mavignier, Ivan Serpa and Abraham Palatnik, who had been looking after the artwork produced at the studio. Later, other classification systems were used in order to enable the search for images according to criteria of interest by the IIM staff, pursuant to Nise da Silveira’s Jungian studies. Glória Chan supported the research team at MII, showing them newspaper clippings and literature in general that Nise da Silveira had collected, and helped them digitalize material relevant to our study. Gladys Schincariol also granted the team an interview and pointed them in the right direction. At the National Library, the periodical section was one of the main sources of articles on the exhibits by the artists from Engenho de Dentro, as well as other documents about the artists that showed an interest in the artistic expression of the group that was emerging in the carioca scene in the 1940s. Mário Pedrosa’s family directed us towards the Mário Pedrosa collection housed at the National Library. There we found photographs of Emygdio de Barros and Raphael Domingues, along with photographs of primitive art and children’s drawings of interest to Pedrosa. Besides these collections, we looked for images and other kinds of documents in several other locations, of which the following stand out: Instituto Moreira Salles, Instituto Philippe Pinel, Instituto Municipal Nise da Silveira, Funarte and Instituto de Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. As data was collected, material was selected according to its relevance and classification. Many hours were dedicated to transcribing the interviews, since Almir Mavignier’s oral narratives needed to be processed from raw recordings in order to produce a textual discourse. Whenever possible, we attempted to identify the references described and relate his reports to the works of the studio artists. As we gathered images from those days, the research gained resonance and became less abstract. Becoming more and more drawn into the research process, we realized we needed to visit the place where the activities of the studio took place. Today, the large well-lit room is subdivided; the walls are covered in white tiles; there is an out-patient clinic there now, with consultation rooms. We photographed some of the few remaining metal chairs and tables that were used during Mavignier’s time, which are represented in Emygdio’s paintings. We also attempted to find early images of the old Pedro II asylum. At present, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) is housed in this historic building, so we were able to walk through the beautiful corridors with handmade blue and white tiles, looking down on the internal courtyards from the second story windows. We observed the refurbishment processes of the building that has been declared a national heritage, and we wondered where the old workshops used to be where wellbehaved patients were granted the opportunity of staying productively occupied. Intrigued by the Santa Teresa streetcar mentioned in Mavignier’s interviews, we went to the neighborhood where the streetcar still operates. We visited the Streetcar Museum and spoke to the manager and other staff members who work at the station near Arcos da Lapa, whose job it is to keep the last Rio streetcar system functioning well. Where had the Grand International Hotel of Santa Teresa been located, where Mavignier had painting lessons with Arpad Szenes? The most probable location we found was at 108 Almirante Alexandrino Street. But it has been torn down. Who were Mavignier’s teachers in Brazil? We acquired catalogues and examined Arpad Szenes and Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s paintings, trying to find echoes of his teachers in the figurative paintings Mavignier produced at that time. In the voice of Quito Pedrosa, Mário Pedrosa’s grandson, we heard stories about his grandfather and his pledge to defend the production of virgin art at the Engenho de Dentro psychiatric hospital. We enjoyed looking at some notebooks he preserved and we gave ourselves up to the sensations of another time. And that is how Mavignier’s story took hold of us, as we sought to listen to his voice, as we let it reverberate within us. |

Contributions of this projectThe study of Mavignier’s interviews raised many issues relevant to the field of art history in regards to the learning of new poetics by Brazilian artists in contact with European artists who lived in Brazil World during War II. Mavignier’s reports clarify important historical notions about the development of artists of his generation and about the diffusion of ideas in open art workshops.

To our understanding, Mavignier’s experiences in an open studio in Rio where Brazilian and European artists came together, reached the painting studio through him, and would become an important influence on the work developed there. The question that instigated our study was: What was it that moved some painters to become interested in the expressive productions of patients in psychiatric institutions during the first half of the 20th century? How did the contact between the artists that were regular visitors at the art workshops in psychiatric facilities affect the visual language of the patients and their own? This kind of inquiry was discussed in master’s theses by Otávio Pompeu e Silva (2006) and also by Rosa Cristina Maria de Carvalho (2008). Carvalho focused on the visual artwork produced at the Escola Livre de Artes Plásticas at Juqueri. The need to investigate further and broaden the discussion of these studies motivated this research project, which has produced results that provide theoretical and methodological support for people who are involved in art activities with vulnerable people. We understand that answers to questions such as these can help us understand the link between the mentally ill and art, the importance of preserving and promoting their work, and also to foster the participation of multi-professional teams in projects of this nature. From another perspective, the results of this project could also help other professionals organize art workshops in Centros de Atenção Psicossocial (CAPs) and other out-patient facilities for people who suffer from mental disturbances and count on the valuable assistance of visual artists. The idea is not to reproduce the work within the context of mental health such as it was engendered between 1946 to 1951, but rather to acknowledge the importance of art professionals working in psychiatric hospitals, in order to strengthen the dialogue between the fields of art and mental health and widely promote the awareness of knowledge related to art manifestations–like those which Dubuffet called l’art brut. |